Saturday, October 30, 2004

Georgia 31 Florida 24

The.Drought.Is.Over. The first win over Florida in seven years. I was worried that Florida would come out as world beaters given the firing of their coach Ron Zook. The question remains: Will one of the most hated people in Georgia return to his old job? |

Thursday, October 28, 2004

Sleepwalking.....

From the October 28th edition of The New England Journal of Medicine comes two papers and two editorials concerning the 80-hour workweek. The authors created what they called an "intervention schedule" where the interns worked no more than 16 hours at a time. The effects on the intern's fatigue and the effect it has on errors. The first: Effect of Reducing Interns' Weekly Work Hours on Sleep and Attentional Failures:

From the October 28th edition of The New England Journal of Medicine comes two papers and two editorials concerning the 80-hour workweek. The authors created what they called an "intervention schedule" where the interns worked no more than 16 hours at a time. The effects on the intern's fatigue and the effect it has on errors. The first: Effect of Reducing Interns' Weekly Work Hours on Sleep and Attentional Failures:

Background Knowledge of the physiological effects of extended (24 hours or more) work shifts in postgraduate medical training is limited. We aimed to quantify work hours, sleep, and attentional failures among first-year residents (postgraduate year 1) during a traditional rotation schedule that included extended work shifts and during an intervention schedule that limited scheduled work hours to 16 or fewer consecutive hours.Would this translate into reduced errors? The paper :Effect of Reducing Interns' Work Hours on Serious Medical Errors in Intensive Care Units attempts to answer the question:

Methods Twenty interns were studied during two three-week rotations in intensive care units, each during both the traditional and the intervention schedule. Subjects completed daily sleep logs that were validated with regular weekly episodes (72 to 96 hours) of continuous polysomnography (r=0.94) and work logs that were validated by means of direct observation by study staff (r=0.98).

Results Seventeen of 20 interns worked more than 80 hours per week during the traditional schedule (mean, 84.9; range, 74.2 to 92.1). All interns worked less than 80 hours per week during the intervention schedule (mean, 65.4; range, 57.6 to 76.3). On average, interns worked 19.5 hours per week less (P<0.001), slept 5.8 hours per week more (P<0.001), slept more in the 24 hours preceding each working hour (P<0.001), and had less than half the rate of attentional failures while working during on-call nights (P=0.02) on the intervention schedule as compared with the traditional schedule.

Conclusions Eliminating interns' extended work shifts in an intensive care unit significantly increased sleep and decreased attentional failures during night work hours.

Background Although sleep deprivation has been shown to impair neurobehavioral performance, few studies have measured its effects on medical errors.This paper describes some of the "serious medical errors" and "nonpreventable adverse events" that range from the tragic to the inane:

Methods We conducted a prospective, randomized study comparing the rates of serious medical errors made by interns while they were working according to a traditional schedule with extended (24 hours or more) work shifts every other shift (an "every third night" call schedule) and while they were working according to an intervention schedule that eliminated extended work shifts and reduced the number of hours worked per week. Incidents were identified by means of a multidisciplinary, four-pronged approach that included direct, continuous observation. Two physicians who were unaware of the interns' schedule assignments independently rated each incident.

Results During a total of 2203 patient-days involving 634 admissions, interns made 35.9 percent more serious medical errors during the traditional schedule than during the intervention schedule (136.0 vs. 100.1 per 1000 patient-days, P<0.001), including 56.6 percent more nonintercepted serious errors (P<0.001). The total rate of serious errors on the critical care units was 22.0 percent higher during the traditional schedule than during the intervention schedule (193.2 vs. 158.4 per 1000 patient-days, P<0.001). Interns made 20.8 percent more serious medication errors during the traditional schedule than during the intervention schedule (99.7 vs. 82.5 per 1000 patient-days, P=0.03). Interns also made 5.6 times as many serious diagnostic errors during the traditional schedule as during the intervention schedule (18.6 vs. 3.3 per 1000 patient-days, P<0.001).

Conclusions Interns made substantially more serious medical errors when they worked frequent shifts of 24 hours or more than when they worked shorter shifts. Eliminating extended work shifts and reducing the number of hours interns work per week can reduce serious medical errors in the intensive care unit.

As intern is preparing to perform a thoracentesis on the left side of the patients chest, the senior resident enters the room and informs the intern that the pleural effusion is on right side of the patients chest.Now JACHO recommends a "time out" for invasive procedures that prevents such things from happening.

Patient with defibrillator implanted on left side urgently needs central access for ionotropic support. Intern inserts a central venous catheter in the left subclavian vein. Not recognizing that the vein contains the wire from the defibrillator, the intern is having repeated difficulty advancing the introducer. In the middle of the placement, the cardiology fellow enters and asks the intern to abort the procedure immediately. The catheter is removed before it can interfere with or dislodge the defibrillator wire.I'm sure the cardiology fellow did more than "ask" the intern to abort the procedure. The phrase "chewed his ass so hard that he needed a colostomy" comes to mind.

A right-sided tension pneumothorax develops after a technical error during placement of a subclavian venous catheter leads to pleural-space puncture.It happens.

The attending physician devised a plan to transfuse a patient for a hematocrit of <30. Despite these instructions, the intern fails to check laboratory results for 36 hours. When the laboratory results are finally checked, hematocrit is found to have been 26 in the interim. The patient has tachycardia for a protracted time as a consequence.Sounds like laziness to me. Kevin does a good job of discussing one of the editorials concerning a weak link in this process, the "check out". From the other editorial:Residency Regulations Resisting Our Reflexes. Sounds like those in academic medicine need a playbill to keep up:

The "bad" weekend is coming up: the pre-call resident is off today, because she is on long call on Saturday and will have to come in post-call on Sunday. She also happens to be postshort call from yesterday, and her absence today means she won't be part of attending rounds when her new cases are presented. Her interns, on the other hand, are here today but will not come in post-call on Sunday; only the resident will come in, and she will round only on the new admissions from Saturday, not the rest of her service. The long-call team must cease taking admissions at 6 p.m. and leave the hospital by 9:30. Night float picks up the admissions from 6 p.m., with a second shift of night float starting at midnight. Thus, there are many more night admissions handed off to the day team on short-call days, which are beginning to resemble long-call days in heft and complexity. The short-call team that is accepting admissions today needs to present its cases to me today instead of tomorrow (in addition to the cases being presented by the resident-less team that is postshort call from yesterday), because they need to be off tomorrow because they are on long call on Sunday.Makes my head hurt. These studies provide short-term results, but the long-range effects of the limits will take years to examine. How will residents that have worked in the "bubble" of workhour limits respond to the "real world" when such limits do not apply? Time will tell. |

Wednesday, October 27, 2004

The Future of Surgery, Redux....

From the September edition of theBulletin of the American College of Surgeons: Changes in resident training affect what you can expect from your next partnerThe treatise begins with an examination of surgical evolution:

I don't believe that Dr. McCoy was the product of an 80 hour work-week limit. Anyway, the critics of the work-week limits have concerns about what is going to be coming out of these programs in the next few years:

The short-term results appear to be good, but this is one of those things that will take several years to shake out.

From the September edition of theBulletin of the American College of Surgeons: Changes in resident training affect what you can expect from your next partnerThe treatise begins with an examination of surgical evolution:

Seventy-five years ago, your next partner would have been described as male and self-sacrificing. He would have done a residency that required that he literally live at the hospital with no time for any other activities and no remuneration. He would have operated in a less-than-sterile environment with a small staff and little more than scalpels and ether with which to work. A surgeon who was just entering practice 10 years ago would have been described slightly differently. Potential partners at this time could have been either male or female. These individuals would have been accustomed to operating in a sterile operating room with many technological resources and a large operating team at the ready. However, one adjective would have remained the same over the years. Surgeons of 10 years ago continued to be seen as self-sacrificing. They would have gone through residencies that still offered minimal remuneration and punishing hours that left little time for family life or other interests. Through the years, these rigorous training regimes were believed to be vital in the production of competent surgeons.How things have changed....

So what will potential partners look like in this century? Everyone hopes for a partner with cool confidence, high-tech capabilities, incisive decision making capabilities, and a slavish devotion to work. A futuristic "Star Trek"-like physician comes to mind. But, with new regulations affecting the number of hours residents may work, the image may be different than expected. The new generation of surgeons will have had limited work hours and will have been required to take less call. They will have been forced to take a day off every week and will have been permitted to sleep after long nights awake. All of these new ways of training residents will definitely affect the way surgeons approach

I don't believe that Dr. McCoy was the product of an 80 hour work-week limit. Anyway, the critics of the work-week limits have concerns about what is going to be coming out of these programs in the next few years:

Whenever change occurs, naysayers start raising their objections. Skeptics of work-hour reform have voiced a multitude of reasons why the reforms are bad for surgical training, including the lack of continuity of care, an erosion of the work ethic, lesser quality of care, a poorer educational experience, weakened skills, and inadequate readiness for practice. These critics portray your next partner as a buffoon with Frankenstein's hands, Homer Simpson's brain, and SpongeBob Squarepants's sense of responsibility.The authors take a contrarian view of that opinion:

It is our contention that if surgical educators make the system more humane, more caring and well balanced surgeons will emerge, and, ultimately, we will see improved patient outcomes and increased student interest in surgery.They end with the "following challenges":

1. Embrace the work-hour regulations as a step in the right direction toward fulfilling our duty to produce whole physicians, ones who heal with compassion and humanity.

2. Look into other ways to promote resident well-being.

3. Study New York City residents to see whether the 405 regulations have affected them.

4. Revamp the education process for residents to fit into the ACGME regulations.

5. Use the changes to attract a broader scope of medical students.

The short-term results appear to be good, but this is one of those things that will take several years to shake out.

Labels: Future of Surgery

|Tuesday, October 26, 2004

From the Mailbag....

A reader emails in:

I recommend you read Natalie's Diary with some perspective from an older surgical resident |

A reader emails in:

I really enjoy your blog. I was wondering if surgicalBest of luck to you as you begin your medical training. There is no official "age limit" for surgical residents. I have worked many excellent surgical residents who started medical school later in life. If your USMLE scores are good and you have good letters, you should be competitive. Will you be competitive at the big academic programs ? probably not as much as you would be at a community-based program. A problem that will concern some programs is that of stamina. Even with the 80 hour limits, surgical residencies can be very exhausting. If you choose to interview at surgery programs, expect some questions about it. Not about your age per se but questions such as, "Did you have trouble staying awake all night?" ect....

residencies are offered to older, non-traditional medical students. I would be starting medical school at 36. Thanks for your time.

I recommend you read Natalie's Diary with some perspective from an older surgical resident |

Monday, October 25, 2004

Celebrity Surgical Watch....

Rehnquist Hospitalized With Cancer in Md.

Rehnquist Hospitalized With Cancer in Md.

Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist, the second-oldest man to preside over the nation's highest court and its premier conservative figure, is undergoing treatment for thyroid cancer.Details are sketchy, but a tracheotomy is not a usual surgical intervention for thyroid cancer. Certainly one would not be expected to return to work within a week. If he had a thyroidectomy, then certainly. As Drudge would say:developing. |

Rehnquist, 80, underwent a tracheotomy at Bethesda Naval Hospital in suburban Maryland on Saturday, the Supreme Court announced Monday. It said he expects to be back at work next week when the court will next be meeting to hear cases.

Thursday, October 21, 2004

Mmmmmmm.....Kool-Aid..

The GruntDoc has a post about the plans for a medical draft. I agree with the GruntDoc here, as does Dr. Smith, and Doc Russia (who posits that "the whole thing is fearmongering by the left to try to woo back voters that normally vote democrat, but are appalled by the choice of a trial lawyer as a Vice President"). If there wasn't a plan somewhere for such a thing, and it was not updated from time to time, the powers that be would be grossly negligent. Just because the plan exists, doesn't mean that it will be implemented.

Mr Cuprisin, however, disagrees:

And from Graham:

Cross-posted at Galen's log |

The GruntDoc has a post about the plans for a medical draft. I agree with the GruntDoc here, as does Dr. Smith, and Doc Russia (who posits that "the whole thing is fearmongering by the left to try to woo back voters that normally vote democrat, but are appalled by the choice of a trial lawyer as a Vice President"). If there wasn't a plan somewhere for such a thing, and it was not updated from time to time, the powers that be would be grossly negligent. Just because the plan exists, doesn't mean that it will be implemented.

Mr Cuprisin, however, disagrees:

The Selective Service and the current administration deny, of course, that any such plan will ever be implemented, but contingency plans are not made for non-existent contingencies. The daily reports of the Army's personnel shortages and the "back-door draft" (the stop-loss policies) already implemented by the Bush administration suggest that some form of draft is a real possibility, regardless of what this President says. (Bush's willingness to mislead the American people is no longer in doubt.)

And from Graham:

I would imagine a significant number of health care professionals-<>doctors, nurses, etc.-would fundamentally be opposed to being sent to war on ethical grounds: that whole concept of killing people and causing harm dont really go too well with the Hippocratic Oath.Graham doesn't have much of an idea of what medical professionals do in the armed services. The physicians in Iraq treat U.S. troops and Iraqi civilians during all phases of Operation Iraqi Freedom. From the September issue of The Journal of Trauma:A U.S. Army Forward Surgical Team's experience in Operation Iraqi Freedom(emphasis mine):

BACKGROUND: The Forward Army Surgical Team (FST) was designed to provide surgical capability far forward on the battlefield to stabilize and resuscitate those soldiers with life and limb threatening injuries. Operation Iraqi Freedom represents the largest military operation in which the FST concept of health care delivery has been employed. The purpose of our review is to describe the experience of the 555FST during the assault phase of Operation Iraqi Freedom. METHODS: During the 23 days beginning 21 March 2003, data on all patients seen by the 555 FST were recorded. These data included combatant status, injuries according to anatomic location, and operative procedures performed. RESULTS: During the twenty-three day period, the 555 FST evaluated 154 patients. There were 52 EPWs, 79 U.S. soldiers, and 23 Iraqi civilians treated. Injuries to the lower extremity and chest (48% and 25%) were the most common in the EPW group. Upper extremity and lower extremity injuries were the most common in the civilian (57% and 39%) and U.S. soldier groups (32% and 30%). The number of injured regions per patient were 1.14 for U.S. soldiers, 1.33 for EPWs, and 1.52 for Iraqi civilians (p <>Majority of the life threatening injuries evaluated involved EPWs. A combination of body armor and armored vehicles used by U.S. soldiers limited the number of torso injuries presenting to the FST. Early resuscitation and stabilization of U.S. soldiers, EPWs, and civilians can be successfully accomplished at the front lines by FSTs. Further modification of the FST's equipment will be needed to improve its ability in providing far forward surgical care.So these dedicated medical professionals aren't kicking the Iraqis to the curb, "killing" them, or "causing them harm". Graham then takes a "don't trust anybody over thirty" tack:

Update: Medpundit and Gruntdoc both say its all over-reaction. Im sure its easy much easier to downplay the concerns of young polyglots, computer network engineers, and medical students when youre over 35, and not at risk of being drafted.To the Times article:

Under the plan, Mr. Flahavan said, about 3.4 million male and female health care workers ages 18 to 44 would be expected to register with the Selective Service. From this pool, he said, the agency could select tens of thousands of health care professionals practicing in 62 health care specialties.While I can't speak for GruntDoc, or Dr. Smith, I certainly fall within that age range. And given my specialty of general surgery with heavy involvement in trauma and vascular surgery, if such a "medical draft" were to be enacted I'm sure my name would be close to the top of any induction lists out there. I'm not worried, I have patients in the here and now to worry about.

Cross-posted at Galen's log |

Wednesday, October 20, 2004

Free markets and Organ Transplantation.....

From ABC: Man Undergoes Web-Arranged Transplant:

Back in August there was the controversy surrounding the solicitation of a liver by Todd Krampitz. The medical blogosphere was divided with Mr. Genes took the position that the current system was flawed, the Grunt Doc takes a position similar to my own, and the Bronch Blogger feels that while it may increase awareness of the need for transplantation, but bad for the organized structure of organ allocation. Dr Rangel came out four-square against the idea:

As for me, I would move heaven and earth, buy all the billboards I could, put it out all over the internet if one of my loved ones needed a transplant. I cannot fault Mr. Krampitz, Mr. Smitty, or Mr. Hickey. While I can't bring myself to support the open market trade of organs for transplant, if the donors and their families feel more "in control" of the destination of their gift, maybe more donations will be offered.

Cross-posted at Galen's Log

From ABC: Man Undergoes Web-Arranged Transplant:

A Colorado man underwent surgery for a new kidney Wednesday in what was believed to be the first transplant brokered through a commercial Web site a transaction that has raised a host of ethical and legal questions.The surgery was delayed because of some concerns that Mr. Smitty was receiving some sort of compensation for his transplant from Mr. Hickey. That appears to be have been resolved since the operation went on. Apparently UNOS can't control the "market" in living-related donors.

Presbyterian/St. Luke's Medical Center spokeswoman Stephanie Lewis said the operation on both the donor and recipient was going well.

Bob Hickey, who lives in a mountain town near Vail, has needed a transplant since 1999 because of a kidney disease. He met donor Rob Smitty of Chattanooga, Tenn., through MatchingDonors.com, for-profit Web site created in January to match donors and patients for a fee.

There are no laws against soliciting an organ donation, but by using the Internet, Hickey bypassed the United Network for Organ Sharing, the nonprofit group that works under government contract to allocate all organs donated from the dead. It doles out organs, in part, according to which patients need them the most.And they are none too pleased:

The network does not oversee the increasing number of live donors, such as Smitty. Last year, there were 6,920 living donors compared with 6,457 dead ones.

UNOS came out against MatchingDonors.com in June, saying it "exploits vulnerable populations and subverts the equitable allocation of organs for transplantation." UNOS spokesman Joel Newman said the network is concerned when anyone puts his or her need for an organ above others.The site may be found here. The rates range anywhere from a "trial membership" of $19.00 for seven days, 30 days for $249, three months for $441, and $582 for six months. There is also some hand-wringing from the ethics crowd:

"An organ that becomes available with certain medical characteristics should be offered equally to the people that could benefit from it," he said.

University of Pennsylvania bioethicist Arthur Caplan said the first ethical issue raised by Internet donations is financial: Not everyone can afford to pay MatchingDonors.com's fees or donor expenses.Shy? Since when did social awkwardness become equated with poverty? One complaint is that the site minimizes the risk to living donors. The risk is easier to take when it is a living-related situation when it is your brother, sister, child, or parent who will be receiving your "gift of life".

"Those who are better off are going to have access to people as potential donors that the poor or the shy won't have," he said.

Back in August there was the controversy surrounding the solicitation of a liver by Todd Krampitz. The medical blogosphere was divided with Mr. Genes took the position that the current system was flawed, the Grunt Doc takes a position similar to my own, and the Bronch Blogger feels that while it may increase awareness of the need for transplantation, but bad for the organized structure of organ allocation. Dr Rangel came out four-square against the idea:

Todd Krampitz essentially bought his liver and screwed who knows which patient likely to be far sicker than Todd out of a chance for a cure of their liver disease and the addition of many years of life. Organ donations that specify the recipient are rare (only about 50 out of thousands of transplants each year) because cadaver organ donation is almost always an anonymous process. Unlike most transplant patients and their families, Todd Krampitz (who owns his own digital photography company) had enough money to pay thousands of dollars for billboard and other ads.Dr. Rangel points out that while Mr. Krampitz may have "screwed" somebody out of a liver, but he was within the rules. Don't hate the player, hate the game.

As for me, I would move heaven and earth, buy all the billboards I could, put it out all over the internet if one of my loved ones needed a transplant. I cannot fault Mr. Krampitz, Mr. Smitty, or Mr. Hickey. While I can't bring myself to support the open market trade of organs for transplant, if the donors and their families feel more "in control" of the destination of their gift, maybe more donations will be offered.

Cross-posted at Galen's Log

Labels: Transplantation

|Tuesday, October 19, 2004

Path of Least Resistance....

With a hat-tip to Graham (like the new look, BTW) for this link to a NPR story on the choices being made by fourth-year medical students across the country:Med Students Seeking Less-Demanding Specialties. Since it's pledge week at NPR I coughed up the $4.95 for the transcript so I can discuss it further.

Here goes:

First off, it's the middle of October. If this guy has no idea of what he wants to do starting in July he is way behind in the ballgame. How many of Mr. Stebbins' classmates are still agonizing over this decision? How many have already filled out their online ERAS applications and how many have already scheduled interviews? Maybe NPR found out about him the same way they found their "swing voter". Mr. Stebbins needs to fish or cut bait or he may be disappointed come Match Day.

Moving along:

What about the fact that fifty percent of medical school applicants are women? Does not that play a role in the career mix of medical students? Or the desire to strive for "balance"? I'll have some more on the "doctors who are afraid to become people's doctor" in just a moment.

Cross-posted at Galen's Log |

With a hat-tip to Graham (like the new look, BTW) for this link to a NPR story on the choices being made by fourth-year medical students across the country:Med Students Seeking Less-Demanding Specialties. Since it's pledge week at NPR I coughed up the $4.95 for the transcript so I can discuss it further.

Here goes:

STEVE INSKEEP, host:

This is MORNING EDITION from NPR News. I'm Steve Inskeep.

For most students, autumn is about buckling down to another year of studies. But fourth-year medical students have to think much further ahead. They have to make decisions about what kind of doctors they want to become. Today more and more medical students are opting to become specialists, raising predictions of a shortage of primary care doctors. To find out why, NPR's Julie Rovner traveled to Mt. Sinai Medical School in New York.....

JULIE ROVNER reporting:

It's been a long day for Bill Stebbins. He's a fourth-year medical student who's just started a new hospital rotation in internal medicine. During a brief break, Stebbins chugs the last of his umpteenth can of soda, delivering another dose of caffeine to his flagging system.

Mr. STEBBINS: And even though you know it has no calories, you know you're feeling good about yourself, that five years down the road you're probably going to die from whatever else is in here.

ROVNER: Stebbins' skin is about the same color as his green medical scrubs, thanks to a combination of a lack of sleep and the overhead fluorescent hospital lights. He looks older than his 26 years, but even with his deadpan delivery, he betrays his amateur status as he prepares to draw an arterial blood gas on a patient.

Mr. STEBBINS: Having blood drawn is not bad but when you dig for the radial artery and you have a moving target who's screaming, you're dealing with a needle as a med student, you know, the pressure's on.

ROVNER: The pressure's on in another part of Stebbins life, too. He has only a few weeks left to decide what kind of medical residency to apply for; in other words, how he wants to spend his medical career.

Mr. STEBBINS: It's a really tough decision to make and it's something that I think about every day and it's causing me mind-blowing amounts of stress, really. Like I've never felt more stressed in my life.

ROVNER: It's a big decision because switching specialties later is hard.

First off, it's the middle of October. If this guy has no idea of what he wants to do starting in July he is way behind in the ballgame. How many of Mr. Stebbins' classmates are still agonizing over this decision? How many have already filled out their online ERAS applications and how many have already scheduled interviews? Maybe NPR found out about him the same way they found their "swing voter". Mr. Stebbins needs to fish or cut bait or he may be disappointed come Match Day.

Mr. STEBBINS: My opinion wavers a lot on a day-to-day basis. If I had to get my obligation in tomorrow, I would specialize in dermatology. I would say that a lot of my decision is based on trying to find a field where I can have enough time to spend with patients and also spending time with my family and raising a family.So serious research in to one's career choice, a career which is demanding regardless of specialty, is not wisely doing one's homework, it is instead "Machiavellian thinking". Especially when it goes against the desires of the academic medical establishment. I remember when I was in medical school there was an emphasis on choosing primary care as a career that bordered on demagogery.

ROVNER: And he wants time for two of his other passions, music and tennis. Bill Stebbins thinks dermatology's nine-to-five schedule will offer him lifestyle heaven. Dr. Larry Smith says he's seeing more and more students like Bill Stebbins. Smith is dean of students at Mt. Sinai on Manhattan's Upper East Side.

Dr. LARRY SMITH (Dean, Mt. Sinai Medical School): I was really unaware of the almost Machiavellian thinking trying to scope out, you know, future incomes, future work hours, preservation of personal time. I realize that something had dramatically changed.

Moving along:

ROVNER: So Smith set out to find out what. He read a series of studies by sociologists done for industry about intergenerational tensions in the workplace. And he discovered that what makes this generation of young doctors different is that they have very different priorities than their baby boomer parents.

Dr. SMITH: They are very much striving for balance. They saw the bad parts of open-ended commitment, which was what it did to their parents. I think the baby boomer generation had a lot of people who went for it 100 percent and became extraordinarily burnt out, were never home and if you just looked at, you know, the current 50-year-old physician, I mean, there's enormous discontent with their life.

ROVNER: Smith says, as a result, students are avoiding time-intensive generalist careers like internal medicine or pediatrics. They're gravitating instead towards specialties like dermatology, radiology and anesthesiology. Those offer more predictable working hours. But Smith says the unpopularity of primary care is about more than not wanting to be on call 24-7.

Dr. SMITH: I think the issue is, I'll be training a generation of doctors who are afraid to become people's doctor, as opposed to the specialist for a disease they may have or a procedure they may need. For a large number of the young physicians, they're fearful of that commitment. And this is really in stark contrast, I think, to a generation before, where, in fact, the concept of being someone's doctor was absolutely at the core of why most people went to medical school.

What about the fact that fifty percent of medical school applicants are women? Does not that play a role in the career mix of medical students? Or the desire to strive for "balance"? I'll have some more on the "doctors who are afraid to become people's doctor" in just a moment.

ROVNER: Back at the hospital, Bill Stebbins career conflict had intensified. He's just experienced for the first time the kind of excitement he's only ever seen on TV.News flash for Mr. Stebbins: you don't always bring them back. Mr. Stebbins has a good point about what the internist has evolved into, a referral center. Why? Because for good or ill, that is what patients want and what the liability climate demands.

Mr. STEBBINS: That was a pretty wild scene. It was my first time ever being part of a code.

ROVNER: A code meaning the patient's heart had stopped. Bill and the rest of the team went to work.

Mr. STEBBINS: It was really exciting. You could feel your heart beating, sweaty, knowing that, you know, it's a time line of minutes.

ROVNER: The patient survived and was sent to recover in the intensive care unit. Bill knows he'd never be part of saving a life that way in dermatology and that's a hard thing to accept. On the other hand, he also knows that being a primary care physician has its own downside.

Mr. STEBBINS: The joys of being an internist when you were the--you know, that person's one doctor are now gone, because you are now the person standing in the way of them getting to the specialist. You know, when anything exciting comes up, your job is to send them to somebody else.

ROVNER: To some extent, today's medical students' desire to have a life outside of medicine is medical schools' own fault. Schools have recruited liberal arts majors like Bill Stebbins. The thinking was that a student with many interests makes a better doctor. Suzanne Rose is Mt. Sinai's associate dean.I would disagree only to the point that I would have said to a "great extent' the schools are to blame. These bright young minds realized early that there was more to life than being a premed student. They see no need to change their hobbies to accommodate their career. The recruitment of more "academically diverse" students was supposed to create not only better physicians but more "humanistic" ones as well. Fewer technocratic biochemisty majors and more "balanced" liberal arts majors. This apparently has not worked as expected if today's students are "afraid to become people's doctor".

Ms. SUZANNE ROSE (Associate Dean, Mt. Sinai Medical School): We have world-class musicians. We've had world-class athletes, somebody that went to the Olympics a few years ago. And some of them are reluctant to give up some of their passions and talents that they had prior to coming here.

ROVNER: Baby boomer Rose is a gastroenterologist by training, one of the first women to pursue that demanding specialty. And she says she went after it with everything she had, sacrificing her other priorities.Medical students are many things, but stupid usually isn't one of them. They can see the increased liability, diminished reimbursement, and other hassles of practicing medicine. They see no need to sacrifice their marriage, family life, or outside interests for what they see as less as a profession, and more of, well, just a job.

Ms. ROSE: I have missed many events in my kid's life. I missed my son's first haircut, which is on video. He's now 19 years old and is doing well. And sometimes he jokes with me that I wasn't really his mother. It was some other nanny that took care of him.

ROVNER: Rose says she's exactly the role model many of today's students don't want. But she's also afraid the balance may be shifting too far in the other direction; that today's students aren't willing to push themselves enough. She recalls one very bright student last year who was looking at some of the easiest programs available.And with the 80-hour workweek limits, he won't have to. The pooh-bahs mentioned above are wringing their hands because of what my landlord refers to as the "Beckham Rule". Medical school and residency have been altered to make them "easier" and "user friendly". And the powers-that-be are shocked, shocked! when students attempt to maximize the ease and user-friendliness of the system. What do they expect?

Ms. ROSE: And I said to him, `Why don't you go to the most academic program you can go to?' And he said, `I don't want to work that hard.' And to me that was shocking. And I said, `What do you mean by that? Don't you want to be the best doctor you can be?' He said, `I'll be great but I don't need to do that. I don't need to work as hard as you worked.'

Cross-posted at Galen's Log |

I have just about completed the paperwork Heimlich Maneuver that is the price to pay for being out of town. More posts later...

Meanwhile, for your viewing pleasure.....John Edwards and his hair!!!! |

Thursday, October 14, 2004

No Place Like Home....

Driving into New Orleans just before Tropical Storm Matthew was an adventure and the flooding cancelled many of the "social program" events such as canoeing and airboat tours that Mrs. Parker was scheduled for. We were able to take the riverboat tour Monday night, however.

Given my interests in trauma, I attended mostly those types of lectures. Monday morning was a symposium on controversies in fluid resuscitation. The thinking has evolved from the aggressive fluid use and the "goal oriented" hyperdynamic resuscitation of Shoemaker to a "less-is-more" approach. Very informative and entertaining.

The afternoon began with the Drake History of Surgery Lecture and the topic was presidential assassinations. The care rendered to Lincoln, Garfield, McKinley, and Kennedy was discussed. While Lincoln and Kennedy suffered lethal injuries there were multiple miss-steps with Garfield's and especially McKinley's care. This was demonstrated by the fact that a patient shot herself and suffered the same injuries that President McKinley had, was operated on by one of the surgeons whom attended the President, and survived.

The last talk was from a panel of military surgeons describing the surgical efforts in Iraq. Capt. Peter Rhee and Capt.Harold Bohman of the Navy medical corps. Col. John Holcomb of the U.S. army, Col. Deborah Mueller of the USAF, and Major Jay Doucet of the Canadian Air force discussed the evolution of the medical treatment and evacuation of combat casualties. I was left with an increased respect for the job that the physicians and nurses caring for our troops do under circumstances best described as austere. There was a personal touch provided by Dr. Rhee when he showed a photo of his brother, a colonel in the Marine Corps, currently in Iraq.

Tuesday was spent in the "Controversial Issues in Trauma" postgraduate course. Well done mostly but one of the speakers gave essentially the same talk he gave the day before. Wouldn't have been much of an issue but the cost of the postgraduate course was $400.

Highly recommended: the Canal St. J.W. Marriott, The Pelican Club, The Redfish Grill, and The Palace Cafe.

All in all, well worth the trip.

Cross-posted at Galen's Log |

Driving into New Orleans just before Tropical Storm Matthew was an adventure and the flooding cancelled many of the "social program" events such as canoeing and airboat tours that Mrs. Parker was scheduled for. We were able to take the riverboat tour Monday night, however.

Given my interests in trauma, I attended mostly those types of lectures. Monday morning was a symposium on controversies in fluid resuscitation. The thinking has evolved from the aggressive fluid use and the "goal oriented" hyperdynamic resuscitation of Shoemaker to a "less-is-more" approach. Very informative and entertaining.

The afternoon began with the Drake History of Surgery Lecture and the topic was presidential assassinations. The care rendered to Lincoln, Garfield, McKinley, and Kennedy was discussed. While Lincoln and Kennedy suffered lethal injuries there were multiple miss-steps with Garfield's and especially McKinley's care. This was demonstrated by the fact that a patient shot herself and suffered the same injuries that President McKinley had, was operated on by one of the surgeons whom attended the President, and survived.

The last talk was from a panel of military surgeons describing the surgical efforts in Iraq. Capt. Peter Rhee and Capt.Harold Bohman of the Navy medical corps. Col. John Holcomb of the U.S. army, Col. Deborah Mueller of the USAF, and Major Jay Doucet of the Canadian Air force discussed the evolution of the medical treatment and evacuation of combat casualties. I was left with an increased respect for the job that the physicians and nurses caring for our troops do under circumstances best described as austere. There was a personal touch provided by Dr. Rhee when he showed a photo of his brother, a colonel in the Marine Corps, currently in Iraq.

Tuesday was spent in the "Controversial Issues in Trauma" postgraduate course. Well done mostly but one of the speakers gave essentially the same talk he gave the day before. Wouldn't have been much of an issue but the cost of the postgraduate course was $400.

Highly recommended: the Canal St. J.W. Marriott, The Pelican Club, The Redfish Grill, and The Palace Cafe.

All in all, well worth the trip.

Cross-posted at Galen's Log |

Friday, October 08, 2004

Money or Justice ??????

From today's Wall Street Journal:As Malpractice Caps Spread, Lawyers Turn Away Some Cases

So is it about "justice for the injured" or about what can be collected? Senator Edwards had the same sort of priorities as well:

And finally:

What is it called when a lawyer does it?

Cross-posted at Galen's Log |

From today's Wall Street Journal:As Malpractice Caps Spread, Lawyers Turn Away Some Cases

Two years ago Shelly Thompson-Mooney, a 35-year-old mother in Texas, died of a cerebral aneurysm. Attorney Roy Key thought her case was a good candidate for a medical-malpractice suit.First of all, as with many anecdotes about alleged malpractice, the devil is in the details and the claim of "substantially the same symptoms" leaves a great deal of wiggle room. The article goes on to describe a legitimate issue with damage caps:

Her common-law husband, Robert Mooney, told the attorney she was brought to the emergency room with substantially the same symptoms she had suffered once before when a blood vessel ruptured in her head. Mr. Mooney said she went three hours without proper treatment. Just over two days later, she died, leaving Mr. Mooney to raise their 4-year-old daughter.

But Mr. Key and other attorneys passed on the case. Ms. Thompson-Mooney was a homemaker, so she had no income the suit could seek to recoup. Her medical bills were covered by insurance, eliminating another potential claim in a lawsuit. That meant a suit probably would need to seek payment for "pain and suffering" -- traditionally a rich vein. But Texas recently had capped awards for such noneconomic damages in the vast majority of medical-malpractice cases at $250,000.

"From an emotional standpoint, I wanted to take the case," Mr. Key says. But he says the cap prevented him from doing so. A case like this one might cost his firm $100,000 to prepare for trial. That is more than the firm had any hope of collecting, since its fee is one-third of any award. "If there was no cap in this state," says Mr. Key, "we would have taken it -- I can say that unequivocally."

Amid the fierce debate over limits on medical-malpractice suits, many states have enacted limits of their own that are having a sweeping impact. One of the most common types -- caps on damages for pain and suffering, or so-called noneconomic caps -- is turning out to have the unpublicized effect of creating two tiers of malpractice victims.Now I'm not saying that caps are a bad thing, just that this is a point to consider if we wish to remain intellectually honest. Some more disparities are pointed out:

Cases involving high earners or big medical bills move ahead. Lawyers can still seek economic damages for the wages these patients lost or to pay for continuing medical bills. But lawyers are turning away cases involving victims that don't represent big economic losses -- most notably retired people, children and housewives such as Ms. Thompson-Mooney.

The effect of such caps became clear to Donald Costello, a lawyer in Santa Cruz, Calif., after he handled two virtually identical breast-cancer cases. Both involved married mothers in their 40s who had two children and died from the disease. One plaintiff was a housewife and her case was settled for $300,000. The other was a Silicon Valley executive whose family won a $2 million settlement....The lawyers are feeling the pain in Texas as well:

One case in Pasadena decided last year involved a mother of two who held a master's degree and worked as a school administrator. She died of an infection following a gastric bypass, and her family won $1.6 million in economic damages.

In the other case, decided this year in San Bernardino County, an unmarried woman on welfare with two minor children died of an infection during a stillbirth after the doctor ignored the patient's symptoms until it was too late. In that case, $200,000 in economic damages was awarded.

Paula Sweeney, a Dallas trial lawyer who has been handling medical-malpractice cases for 23 years, says the caps have already slashed her business. Since the beginning of the year, she's filed only one case. In a normal year, she would have filed 12 to 15 by now. "The economic feasibility has changed," she says. She says she believes the new restrictions will eliminate about 85% of medical-malpractice cases in the state.There are ways of estimating such things, some serious, and some not so serious. It is probably not as difficult as it would seem. Caps on non-economic damages work for two reasons, one of course is the limit of the overall sum. The other is that economic damages are relatively easy to calculate, and the uncertainty of punitive/non-economic damages is eliminated.

Trying a case typically involves hiring half a dozen expert witnesses and costs about $100,000, she says. Under the state's new pain-and-suffering cap, that essentially eliminates any case where the victim had no income or no continuing medical expenses. Lawyers use economists to try to quantify "mommying activities," such as chauffering and cooking, to argue for economic damages, but that can be difficult and often doesn't amount to much

So is it about "justice for the injured" or about what can be collected? Senator Edwards had the same sort of priorities as well:

Over time, Mr. Edwards became quite selective about cases. Liability had to be clear, his competitors and opponents say, and the potential award had to be large.

"He took only those cases that were catastrophic, that would really capture a jury's imagination," Mr. Wells, a defense lawyer, said. "He paints himself as a person who was serving the interests of the downtrodden, the widows and the little children. Actually, he was after the cases with the highest verdict potential. John would probably admit that on cross-examination."

The cerebral palsy cases fit that pattern. Mr. Edwards did accept the occasional case in which a baby died during delivery; The North Carolina Lawyers Weekly reported such cases as yielding settlements in the neighborhood of $500,000. But cases involving children who faced a lifetime of expensive care and emotional trauma could yield much more.

And finally:

For plaintiffs' attorneys, the primary question in cases involving babies and others without income is whether medical needs are continuing. That boosts a potential award because it wouldn't be limited by the cap on noneconomic damages. The question proved crucial for Brenda Stoltz, of Leesburg, Va. Ms. Stoltz says a botched delivery last year left her daughter, Zoe Elizabeth, severely brain damaged.If a physician had done what was described above, it would rightly be construed as abandonment.

During delivery, there were signs that the baby was in distress, including an extremely slow heart rate over an extended period of time, according to Ms. Stoltz. Yet no emergency C-section was done. This lack of action and other errors, says Ms. Stoltz, left Zoe deprived of oxygen during a critical period. She was born with severe brain and other organ damage.

Last September, Ms. Stoltz and her husband decided to sue the doctor involved and they retained a Maryland law firm that specializes in medical malpractice. Zoe was facing a lifetime of expensive medical care.

But on Oct. 21, Zoe died. Ms. Stoltz says she told the lawyers of her baby's death the next day. Shortly after that, the firm dropped the case. A lawyer for the firm wouldn't comment.(emphasis mine)

What is it called when a lawyer does it?

Cross-posted at Galen's Log |

The Battle of New Orleans.....

This is where I'll be until Wednesday:

I am taking the laptop so there may be a post or two from Rue Burbon.... |

This is where I'll be until Wednesday:

I am taking the laptop so there may be a post or two from Rue Burbon.... |

Thursday, October 07, 2004

The Future of Surgery III.....

The final commentary on the Annals of Surgery piece.Surgical Education in the United States: Portents for Change. As an aside, I apologize for the lack of a free link. Since there is no abstract in this paper Medline only has the citation. This post analyzes the paper's statements concerning general and specialist surgeons.

However community general surgeons as a group seem to realize this themselves:

Speaking of the specialist surgeon:

Cross-posted at Galen's Log

The final commentary on the Annals of Surgery piece.Surgical Education in the United States: Portents for Change. As an aside, I apologize for the lack of a free link. Since there is no abstract in this paper Medline only has the citation. This post analyzes the paper's statements concerning general and specialist surgeons.

It was suggested as recently as 1998 that most leading surgeons in the country still believe that broad surgical training is superior and should be maintained. It is not surprising that a group (79%) of surgeons older than 50 years would support the regimen that molded them!I was not aware that the number of surgeons who specialize was that high. There are multiple fellowships that surgical residency graduates can pursue ranging anywhere from 1 to 4 years. Specialization offers the potential of higher pay, better hours, and the ability to engage in an area of practice which one really enjoys. As noted above, even more surgeons "self-differentiate" as they stay in practice. While some may obtain new skills and concentrate their efforts there, more often it is by eliminating areas of their practice as time goes by. Many stop covering trauma, performing cancer procedures, or otherwise shrink their "sphere of influence". The reasons are many: fear of liability, group dynamics (you have fellowship trained associates that concentrate their practice), community dynamics (other fellowship trained surgeons in town), geography (proximity to an academic medical center), and facilities (does your hospital have the staff and physical plant capable of handling things?).

The general surgeon, the hallowed product of surgical training in this country, is a vanishing breed. More than 70% of surgeons completing general surgical residency opt for subspecialty training immediately after residency, and an even greater majority self-differentiate by the time of first recertification.

Those surgeons who remain as classic general surgeons have a practice that barely resembles what they were trained to do. A recent analysis of the workforce patterns of rural surgeons in West Virginia suggested that more than half were so discouraged that they would not encourage a young person to pursue a career in medicine. More than one third of these surgeons practiced some general medicine daily, and the surgical caseload varied by community size. In communities of fewer than 10,000, they listed obstetrics and gynecologic (9%), urological (5%), otolaryngology (9%), and orthopaedic (4%) procedures as part of the regular caseload. Endoscopic procedures comprised 17% to 24% of total procedures regardless of community size, which is clearly not a focus of the current general residency education program.One must remember that during the time this survey was taken West Virginia was embroiled in a liability insurance controversy which could explain the 50 percent dissatisfaction described above. In smaller communities there are often not ant gynecologists, otolaryngologists, urologists, or other orthopedic specialties. Endoscopy is attractive to surgeons because it is quick, easy, and can lead to other procedures. There is a large body of research that shows, quite frankly, there are some procedures that the community general surgeon has no business performing:

Other general surgeons believe that they should be trained and encouraged in all surgical practices, particularly gastrointestinal surgery. Academic reports and societal demands, however, emphasize that the casual operator has morbidity and mortality rates unacceptable for major procedures such as esophagectomy, pancreatectomy, and liver resection. High-volume surgeon and institutional experience improves operative mortality, morbidity, and long-term survival. That 25% of patients undergoing pancreatectomy are operated on by surgeons who perform less than 1 procedure a year, and that 96% of surgeons who performed a pancreatectomy in the State of New York between the years 1983 and 1991 performed 1 or fewer annually, is hardly desirable patient care.This raises again the issue I brought up in this post, that patients with the motivation and means to find themselves a "center of excellence" will receive better care.

Is it possible or even appropriate to train generalists to do such procedures when so few exist in the majority of residency training programs in this country? The converse argument is that while we wish that complex procedures be performed in high-volume centers, it will just not happen; eg, in a study of Medicare patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy 28% of patients had their procedure performed at an institution that did less than 1 a year and 80% had an operation in an institution that did less than 5 a year. However, because it is so does not mean it is the desired aim. Ask the patient! It is becoming clear that when patients have information and the possibility to choose, they will choose centers with better outcomes. Analyzing this issue from the pure perspective of where the operation has been performed is flawed, because it incorrectly assumes that patients had both information and the possibility to choose.

The generalist is in part damned because he or she is judged against the outcome results of the specialist.(emphasis mine)

However community general surgeons as a group seem to realize this themselves:

The general surgeon, even in the absence of any fellowship training, self-differentiates. Of surgeons presenting at 10 years for recertification, the average number of hepatic and pancreatic procedures per year was less than 1, 86% did no liver procedures, and 79% had not performed a pancreatectomy. Procedures for which the median annual experience was zero included esophagus, liver, any transplant, splenectomy, and any complex vascular procedure. Even if we believe that the generalist should do it all, the general surgeon and the patient have decided otherwise.But the desire for patients to all go to a "center of excellence" for a particular procedure, gets splashed in the face with the ice water of reality:

It is clear that we cannot mandate where common operations be performed. It is estimated that if colectomy was limited to hospitals doing a minimum of 15 procedures in 5 years, 1400 patients (5% of the total) would be redirected and 263 hospitals (45%) would discontinue the procedure, and the operative mortality would fall from 4.59% to 4.44%.As I pointed out here this study cited a false-negative rate of appendectomy in children of 4.8 percent in high volume centers, compared to 8.4 percent overall. The 4.8% was reached only in 13 out of 2521 hospitals that contributed data, and those hospitals accounted for only 5.6 percent of the procedures analyzed. Hope you like to travel. There are also implications for training future surgeons in those types of procedures:

More frightening is the question of where might these procedures be performed in sufficient volume to train anyone? In a previous study, only 27 hospitals in the nation did more than 16 pancreatic resections a year, which strongly argues for using these uncommon cases to train only those who will fully embrace this type of practice.So what do I do all day?

What are the recertifying general surgeons doing? In part, it depends on the population, but in the main, it is endoscopy, breast, cholecystectomy, hernias, and appendectomy.In an ironic twist to all this, many trauma attendings in university settings are acting like community surgeons and handling general surgical emergencies while on call in an attempt to maintain skills. Of course there will now be a cry for an "emergency surgery" fellowship.

The need for general surgical leadership in clinical practice is very real. It is clear that the general surgeon, whether practicing in small communities or large, remains an important bastion in emergency management of inflammatory conditions such as acute cholecystitis or acute diverticulitis and in initial management of the burned or otherwise injured patient. All of these areas progressively demand the resources of specialized centers and specialized surgeons so that patient outcome can be maximized.

Speaking of the specialist surgeon:

Seventy percent of male surgeons and 50% of female surgeons completing a surgical residency go on to subspecialty training. Many argue that the general surgical experience provides little beyond a basic understanding of surgical principles that prepares them for a subsequent career in a focused discipline. Urology, orthopedics, and neurosurgery take a 1-year internship and then move directly to their own discipline. Would it not be better if we served the needs of all potential surgical faculty with a structured introductory surgical component and then allowed early differentiation?Are urologists, orthopedists, and the like included in that seventy percent? I doubt it.

The demand for greater cultural training in communication and humanistic as well as technical skills is increasing, but does the dedicated cardiothoracic surgeon need to do one pancreatic resection or total gastrectomy to prepare him or her for a career in which he or she will rarely, if ever, see the organ, let alone operate on it? Many surgical residents who go on to specialty training see at least 2 of the 5 years spent in general surgical training as a waste of the most productive years of their lives, which could be dedicated to their specialty or to research within that specialty. Plastic surgery has experimented with 1, 3, or 5 years of a general surgical program before moving on to a dedicated 2- to 3-year course in plastic and reconstructive surgery. An analysis of the participants in each of these pathways would provide great insight into the merits of each approach.So we are taking operations that are rare (pancreatic resection and gastrectomy) and have a direct outcome-volume relationship, and "forcing" residents that have little or no interest in performing them outside of training to do them while they (the residents) could better spend that time with other endeavors. Some surgical specialties are moving beyond the traditional "blade and suture" approach, while also trying to maintain traditional general surgical skills:

Advances in science and technology are forcing the melding of specialist practices. The training required in vascular surgery needs to be meshed with that of interventional radiology, and combination residencies have been promulgated. A similar dilemma will exist in other image-guided therapies. Conversely, if one wishes to practice general surgery in addition to the specialty field, as has been suggested by one third of current vascular surgeons, how do we address the need for the vascular surgeon to be appropriately and adequately trained for the general surgery practice that he or she desires to pursue?There are also serious implications for re-certification:

The demands for analysis of competency, whether in training, generalist, or specialist practice, will add further burdens to the limits to which comprehensive all things to all people training can be maintained. How appropriate is it to demand of a vascular surgeon that he or she be recertified in general surgery, or that a general surgeon be recertified to include the elements of vascular surgery that he or she no longer practices? What of the person who has dedicated his or her life to the management of breast disease, who is asked to be recertified in the broad discipline that he or she initially embarked upon? Testing surgeons in areas in which they do not practice defeats the goal of recertification or continuing education. How much does recertification in a comprehensive generalist sense, when personal focus is highly specialized, deter re-evaluation and assessment of competency?In addition to this there are calls for increasing the requirements for recertification, such as submitting charts, CE "modules" and videotapes of operations. When does the desire to insure competency become an onerous burden? It will take years to work these issues out, and I see stormy weather ahead.

Cross-posted at Galen's Log

Labels: Future of Surgery

|Wednesday, October 06, 2004

Now you see it...

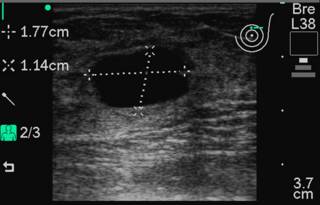

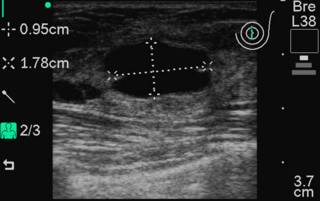

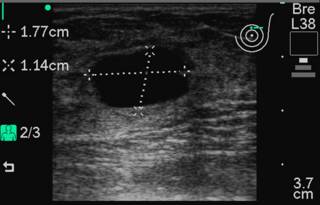

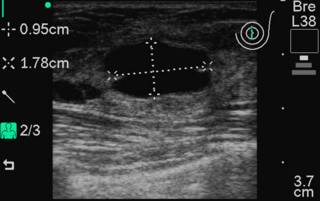

On call last night so no big post until later. This could also be titled "Fun with In-Office Ultrasound". 36 y/o with painful breast mass. Mass at 12:00 position left breast. Here are the transverse and sagittal projections obtained with a Sonosite 180:

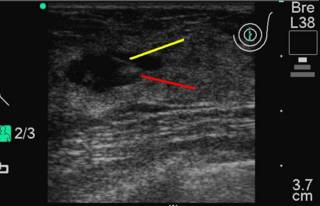

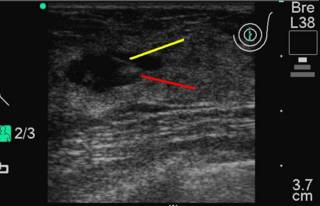

FNA performed with a 25 gauge needle:

Yellow line is the needle, red line is the swirl artifact of the fluid.

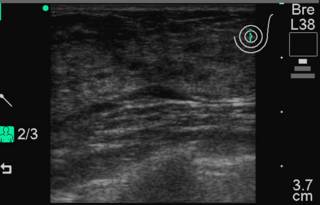

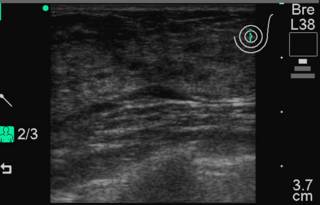

And now it is gone!

|

On call last night so no big post until later. This could also be titled "Fun with In-Office Ultrasound". 36 y/o with painful breast mass. Mass at 12:00 position left breast. Here are the transverse and sagittal projections obtained with a Sonosite 180:

FNA performed with a 25 gauge needle:

Yellow line is the needle, red line is the swirl artifact of the fluid.

And now it is gone!

|

Tuesday, October 05, 2004

Travelin' Man...

My ideal dream job in medicine would be that of a professional fourth-year medical student. You can sample all sorts of specialties for short periods of time, have little real responsibility, and you have the security of being the smartest you have ever been. The fourth year of medical school also allows for the ability to engage in "away rotations". This provides one with the means to "see the world" while paying in-state tuition. Some students do rotations at institutions where they may want to eventually serve as residents. But medical liability is beginning to raise it's ugly head here. From Overlawyered and the Raleigh News & Observer:

Correction: An alert reader pointed out my mistake in the above post. The Mayo School of Medicine has the smallest class. Thanks for pointing that out. |

My ideal dream job in medicine would be that of a professional fourth-year medical student. You can sample all sorts of specialties for short periods of time, have little real responsibility, and you have the security of being the smartest you have ever been. The fourth year of medical school also allows for the ability to engage in "away rotations". This provides one with the means to "see the world" while paying in-state tuition. Some students do rotations at institutions where they may want to eventually serve as residents. But medical liability is beginning to raise it's ugly head here. From Overlawyered and the Raleigh News & Observer:

The malpractice issue has had a negative influence, however, in the kinds of learning opportunities medical schools offer. In years past, Halperin said, schools routinely let students do training stints at hospitals around the country. Now this practice is being curtailed, because medical schools are leery of carrying the liability for students working outside their hospitals.The article points out that medical education remains in high demand in North Carolina:

Such subtle problems seldom get mentioned in the debate, but Halperin said the effect is long term. "It's inhibiting access to educational opportunities," he said.

Now, there is no shortage of students wanting to become doctors. At Duke University School of Medicine, 5,000 students applied last year for 101 slots; at UNC's medical school, 2,972 students vied for 160 slots; at East Carolina University, 705 competed for 72 openings.Those numbers mainly reflect the quality of the medical education at Duke and UNC more than it reflects the "glut' of applicants. In 2003 there were 34,786 applicants and 392,118 applications (data here) so each applicant filled out 11 applications, on average. The 34,786 applicants was an increase of 3.5 percent from last year, but nowhere near the high of 46,965 in 1996. The application numbers are interesting. The school with the most applications in 2003 was George Washington University with 9,132 applicants, the least was Brown University with 162. The University of Illinois had the most matriculants with 313 and the smallest class, consisting of 46 students, was at the FSU College of Medicine, a medical school started in 2000.

Correction: An alert reader pointed out my mistake in the above post. The Mayo School of Medicine has the smallest class. Thanks for pointing that out. |

Monday, October 04, 2004

The Future of Surgery II...

Continuing the discussion of this article from the October 2004 Annals of Surgery: Surgical Education in the United States: Portents for Change. This post will discuss the changes in surgical education on medical students, residents, and academia. First the students:

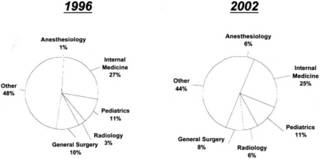

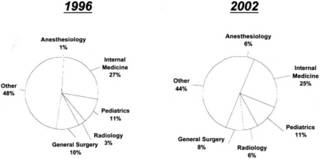

Medical school career choices, ranking specialties, 1996 vs 2002:

As for the residents:

Now to academia:

The final post will concern general and specialist surgeons.Cross-posted at Galen's log

Continuing the discussion of this article from the October 2004 Annals of Surgery: Surgical Education in the United States: Portents for Change. This post will discuss the changes in surgical education on medical students, residents, and academia. First the students:

For medical students, surgery has become an increasingly unappealing area of medical practice. The National Residency Matching Program suggests that from 1992 to 2000, the numbers ranking general surgery as a preferred discipline fell from 1950 to 1500, an overall decrease of approximately 23%. For US seniors, the fall has been more dramatic, on the order of 36%. The only increase has been in US citizens educated in international medical schools. This number reached a maximum of 140 individuals as of 2002 and, although its overall impact is limited, the impact in terms of the quality of applicants for surgical programs is real. An increase in international medical graduates can compensate for this shortage, but it has inherent problems in terms of the difficulty in evaluating foreign graduate medical education and increasing immigration service review of foreign access to US surgical programs. Active programs to improve international medical graduate performance are currently under way.The NRMP data may be found here on page four. While the trend has improved somewhat, surgery has not regained the popularity it once had.

Students shun the rigors of surgical training and view the profession as too demanding and providing little opportunity for personal time. From 1996 to 2002, controllable lifestyle explained 55% of variability in specialty preference, controlling for income, work hours, and years of graduate medical education. Medical student choices have changed to user-friendly specialties. Currently, the median debt at completion of medical school is over $100,000 . Over 25% of medical school graduates of 2002 incurred a debt greater than $150,000.13 The prolonged length of surgical training, fellowship, and research experience, requiring 9 to 11 years post-MD at subsistence pay, is poorly perceived, and a strong belief that years are wasted in service without education is a strong disincentive.So based on the above, over half of medical students based their specialty choice on the perceived control over lifestyle. Needless to say, general surgery is not well known for having a "controllable lifestyle". That is not likely to change even with "reforms". Such specialties as anesthesia, radiology, and emergency medicine have excellent lifestyle control mechanisms. Surgery residency is already five long years with some programs requiring more time, and with workhour limits, it may grow even longer. Not exactly a move that will suck the medical students in.

Medical school career choices, ranking specialties, 1996 vs 2002:

A powerful factor in the choice of medical specialty is identification with role models. Role models are the impetus to entry into a surgical subspecialty in 56% of residents. What makes an ideal role model has been debated and defined Role models can be introduced at any point in a training program, perhaps best in medical school. How well do we as surgeons match up to the important attributes that emphasize, as in internal medicine, dedicated time as a teacher, doctor-patient relationships, the teaching of psychological aspects of care, and prior chief resident experience?Surgeons match up pretty poorly when compared with other specialties in reference to "dedicated time as a teacher, doctor-patient relationships, the teaching of psychological aspects of care". It probably has to do with the personality types that migrate into surgery. Want examples? Look at this post comparing the "pimping" styles of internists and surgeons.

As for the residents:

Whether surgeons of our vintage appreciate it or not, an inescapable change has taken place in today's residents with respect to their perceived needs for a balanced lifestyle that allows more time with families and free time to follow their interests. We dismiss the lifestyle needs of residents at the peril of our recruitment success.Give the NRMP data, postgraduate surgical education has become a "buyers market".

Over the years, residents have accumulated more and more administrative chores, many of which make little sense in an environment that is so rich in information systems. Processes by which patients are admitted, cared for, and discharged are antiquated, take minimal advantage of information technology, and impose an unjustifiable burden on residents. These processes need to be totally revised and adapted to current needs. Surgical education has to be more about understanding, imagination, and communication as well as training and skill acquisition. Surgical training programs are perceived as being none of these, but rather focused on service delivery, particularly to the poor and underprivileged. At present, 20% of surgical residents taking the American Board of Surgeons Qualifying examination are female, whereas females constitute 50% of the medical school graduates. The overall contribution of women to the long-term workforce in surgery is limited appropriately by the desire and need for a lifestyle that can accommodate childbearing and childrearing without limiting professional satisfaction. Few residencies have innovative programs to address the important need of women residents and that of male-resident fathers whose spouses have a full-time professional career. The desire for women to enter surgical subspecialties is variable, with increases in female orthopaedic residents lagging behind increases in other areas. We need to recognize that many medical students approach residency together as a couple, requiring adaptability in the residency match. How well can we adapt to this 2-person professional medical family?How well surgical education adapts to these issues will determine the future of the practice of general surgery.

To compound this perception of too little time to learn too much, we impose volume requirements for each resident that are difficult, if not impossible, to meet. The extensive clinical spectra to be covered by any one resident make any proposed decrease in the length of training difficult. We have been reluctant to acknowledge that most institutions and residencies cannot provide the volume and breadth of clinical material that we demand they be exposed to!I agree. I remember readying myself for the boards, both written and oral, and having to review a good deal of head and neck surgery. I had done maybe 2 radical neck procedures. This is one reason that the American Board of Surgery has initiated an Early Specialization Program . This allows those wishing to pursue specialization in pediatric or vascular surgery to reach their goal 1 year earlier than planned. Some programs also exist for plastic surgery and maybe soon in thoracic surgery.

The resident facing his board examinations may be justified in complaining when he or she is examined in technical aspects of pancreatic, esophageal, or infected aorto-iliac graft surgery that he or she has rarely seen and never performed.

Now to academia:

Teaching can impose a degree of inefficiency in the provision of hospital services, and typically the cost structure of teaching hospitals is 25% to 30% higher than that of community hospitals. Thus, hospitals will scrutinize and demand appropriate reimbursement for the cost of this necessary inefficiency if they are to survive in an arena of brutal health market competition.In the modern era of evidence based medicine and efficiency, the academic medical center operates at a severe disadvantage. Turnover in departments is increasing as the emphasis moves from teaching to production.

Faculty in medical schools already demonstrate a 30% level of high emotional exhaustion and burnout, with younger surgeons more affected! Given the current faculty workload of between 60 and 80 hours per week, it is unlikely they can absorb more teaching and clinical cases. Exhausted faculty are poor role models!

Residency programs are the pride of academic surgical departments and provide the single most important focus for faculty unity. As reimbursements for physician services decline and faculty work longer hours and cope with increasing documentation, their ability to devote adequate time to teaching and other scholarly activities has been strained. Most departments do not make specific financial commitments for teaching. It is fortunate that faculty members receive gratification from teaching and their association with residents in the care of sick patients. The lack of specific compensation for teaching will in the long term degrade the learning environment and challenge the traditional ad hoc understanding under which surgical education is provided. How and by whom should surgeons be financially compensated for the teaching they do? How will we accept that the process of education is an equally fruitful source of research and evaluation? A desirable pathway to surgical fulfillment is currently poorly recognized and inadequately compensated.

The final post will concern general and specialist surgeons.Cross-posted at Galen's log

Labels: Future of Surgery

|Sunday, October 03, 2004

The Gift that Keeps on Giving...

From the Atlanta Journal-Constitution: Emory methods questioned

Cross-posted at Galen's Log |

From the Atlanta Journal-Constitution: Emory methods questioned

Emory University Hospital has not adopted the most rigorous type of sterilization of surgical instruments after learning Sept. 15 that a brain surgery patient may have spread a fatal ailment that resembles mad cow disease to more than 500 patients, a federal health official said Friday.The ideal sterilization protocol would involve sodium hydroxide as well as increased heat. Emory objects to the use of NaOH due to its' corrosive nature and has concerns about the durability of disposable instruments. This is going to be a tough spot for Emory to overcome, as every time these patients have a dizzy spell or memory loss they will be struck with the frightening possibility that they could be manifesting CJD.

The best medical sterilization measures call for a chemical Emory is not using, plus more intense heat, said Dr. Ermias Belay, an epidemiologist with the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta. Belay helped write the sterilization guidelines.

Emory also waited two weeks after the initial patient's probable diagnosis of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease before informing other patients they may have been exposed, subjecting dozens of people to brain or spine surgery without their knowledge of the risk.

"I think we had every right to be informed," said Susan Nabulsi of Conyers, whose husband, Mike Nabulsi, had neck surgery Monday, long after Emory knew of the concern. "We were not given an informed choice."

In all, 516 patients are facing an uncertain future, knowing that years from now they could develop a fatal disease for which there is no treatment, even though the risk is small.

Cross-posted at Galen's Log |

Saturday, October 02, 2004

Georgia 45 LSU 16

The No. 3 Bulldogs whipped No. 13 LSU in every aspect of a 45-16 victory in which their big-name players produced big-time in their biggest game this season. Making things sweeter for Georgia: It scored more points than any team LSU has faced since 1996, a testament to how explosive the Bulldogs can be when everything clicks.I missed a good deal of the game since I was on call. I hope they play this well for the rest of the year. |

Friday, October 01, 2004

The Future of Surgery...