Tuesday, May 31, 2005

Monday, May 30, 2005

Where Do You Draw the Line?.....

From Overlawyered comes a link to this story from the Boston Herald concerning a lawsuit against the NBME over how it conducts the USMLE. The story is archived, but hey, it only cost four bucks:

So this young lady wants accommodation to retake the USMLE I for the fourth time.

So what's next? I find the "no big deal"line amusing as well: "They make it seem like the world will come to an end, as if she's going to operate the next day," her attorney said. "All this does is let her go on to her third year of school."No "all this does" is set up a precedence so when it come time to take step 2 or 3 or her board certification she will be able to demand special accommodation.

I'm sorry but the ability to process information under pressure is a key component of the practice of medicine. During a code you can't get a "do over". As this Virginia Postrel article points out not all accommodations are created equal:

Sorry to say, but not everyone is cut out to be a physician. Some find this out during undergraduate when organic chemistry gets too hard, others when the MCAT doesn't go their way, some drop out after gross anatomy. The system has a way of "weeding out" those that don't have the talent or temperament to practice medicine. Medicine, like aviation for example, is different than many other professions in that mistakes can be costly. Our critics point out the sometimes poor job we do of policing ourselves. If the NBME doesn't do it, who will? The specialty board? A hospital credentials committee ten years down the road?

The future safety of patients trumps any "dream" that this young lady may have. |

From Overlawyered comes a link to this story from the Boston Herald concerning a lawsuit against the NBME over how it conducts the USMLE. The story is archived, but hey, it only cost four bucks:

Med student's dyslexia plea: I need time to pursue dream

By J.M. Lawrence

With an IQ higher than 99 percent of the population, Heidi Baer's school days should be a breeze. But the Quincy woman says she fought through reading disabilities and dyslexia to graduate from Milton Academy and barely get into med school.

Now her dreams of becoming a doctor like both of her parents could end next week unless a federal judge orders a national board to give her extra time for her fourth attempt at passing her second- year exams, her attorney said.

"Not to give her the extra time would be testing her disability, not her mastery of the information on the test," her attorney, Bret A. Cohen, said yesterday. Baer is suing under the Americans with Disabilities Act.

The National Board of Medical Examiners, however, says messing with the test would compromise standards and might even "put patients at risk."

The board's attorneys this week asked U.S. District Court Judge George A. O'Toole Jr. to reject Baer's request for time and a half to complete the May 5 test, which she already has flunked three times at Drexel University in Philadelphia.

"They make it seem like the world will come to an end, as if she's going to operate the next day," her attorney said. "All this does is let her go on to her third year of school."

Cohen said the 30-year-old woman should be commended for her struggle but noted her previous failures on the exam always will be reported to hospitals where she seeks internships.

The medical board's experts rejected claims by five doctors and a psychologist who found Baer has learning disabilities. The board's Dr. Joseph E. Bernier, who reviewed Baer's testing histories, declared her reading abilities average and pointed out that she managed to do the SAT without extra time.

After failing the medical school entrance exam, she was given extra time in 1999 and passed.

Baer is now taking an intensive test preparation course in Chicago for her second-year exams and could not be reached for comment yesterday. Drexel officials usually impose a three-strikes rule on med students but are giving Baer another try.

The judge is expected to rule in the case next week.

So this young lady wants accommodation to retake the USMLE I for the fourth time.

So what's next? I find the "no big deal"line amusing as well: "They make it seem like the world will come to an end, as if she's going to operate the next day," her attorney said. "All this does is let her go on to her third year of school."No "all this does" is set up a precedence so when it come time to take step 2 or 3 or her board certification she will be able to demand special accommodation.

I'm sorry but the ability to process information under pressure is a key component of the practice of medicine. During a code you can't get a "do over". As this Virginia Postrel article points out not all accommodations are created equal:

Over the past decade students with learning disabilities have gotten used to having extra time on tests and, in some cases, separate rooms to reduce distraction. In many cases that makes sense. Giving a dyslexic third grader extra time on a standardized test makes it more likely that his answers will show what he knows rather than how fast he reads.And we all know physicians like that. They worked through their disability without the need for accommodation.

But a sensible accommodation for little kids can create a misleading double standard for adults. How much you know isn't the only thing that matters in school--especially when you're training for a demanding professional job. What patient wants a genius doctor who can't focus in a distracting environment, reads so slowly that she can't keep up with medical journals or tends to misspell drug names on prescriptions?

There are, of course, excellent physicians with learning disabilities. But they succeeded the hard way, without special accommodations. They demonstrated that they could work around their problems.

The lawsuit ignores the nature of medical training, which is notoriously grueling for a reason. Patients' lives depend on physicians' ability to perform under pressure. If learning-disabled students can't do well on a timed test, maybe they aren't suited to be doctors.Another good point:

Irrelevant, says Tollafield. "The MCAT is not a test that's designed to predict how you would do as a doctor. It's designed to predict how you'll do on other tests in medical school and the grades that you'll earn."

That argument denies the fundamental reality of professional schools. No matter how theoretical their classes, these programs aren't about learning for learning's sake. They're trade schools that prepare and certify people for demanding jobs. In those jobs, performance--not intelligence or knowledge--is what matters.

Besides, the disability rights people have no objection to the most blatant form of educational discrimination: the prejudice against people who, thanks to the genetic lottery, aren't exceptionally bright.

For an aspiring doctor, average intelligence is a far greater handicap than dyslexia or attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Why do some brain attributes matter more than others? Why, to use the trendy jargon, should we "privilege" intelligence?

"Wow," says Tollafield. "That's a big policy question. I don't know that I'm capable of answering it."

Sorry to say, but not everyone is cut out to be a physician. Some find this out during undergraduate when organic chemistry gets too hard, others when the MCAT doesn't go their way, some drop out after gross anatomy. The system has a way of "weeding out" those that don't have the talent or temperament to practice medicine. Medicine, like aviation for example, is different than many other professions in that mistakes can be costly. Our critics point out the sometimes poor job we do of policing ourselves. If the NBME doesn't do it, who will? The specialty board? A hospital credentials committee ten years down the road?

The future safety of patients trumps any "dream" that this young lady may have. |

Memorial Day.....

HEADQUARTERS GRAND ARMY OF THE REPUBLIC|

General Orders No.11, WASHINGTON, D.C., May 5, 1868

The 30th day of May, 1868, is designated for the purpose of strewing with flowers or otherwise decorating the graves of comrades who died in defense of their country during the late rebellion, and whose bodies now lie in almost every city, village, and hamlet church-yard in the land. In this observance no form of ceremony is prescribed, but posts and comrades will in their own way arrange such fitting services and testimonials of respect as circumstances may permit.

We are organized, comrades, as our regulations tell us, for the purpose among other things, "of preserving and strengthening those kind and fraternal feelings which have bound together the soldiers, sailors, and marines who united to suppress the late rebellion." What can aid more to assure this result than cherishing tenderly the memory of our heroic dead, who made their breasts a barricade between our country and its foes? Their soldier lives were the reveille of freedom to a race in chains, and their deaths the tattoo of rebellious tyranny in arms. We should guard their graves with sacred vigilance. All that the consecrated wealth and taste of the nation can add to their adornment and security is but a fitting tribute to the memory of her slain defenders. Let no wanton foot tread rudely on such hallowed grounds. Let pleasant paths invite the coming and going of reverent visitors and fond mourners. Let no vandalism of avarice or neglect, no ravages of time testify to the present or to the coming generations that we have forgotten as a people the cost of a free and undivided republic.

If other eyes grow dull, other hands slack, and other hearts cold in the solemn trust, ours shall keep it well as long as the light and warmth of life remain to us.

Let us, then, at the time appointed gather around their sacred remains and garland the passionless mounds above them with the choicest flowers of spring-time; let us raise above them the dear old flag they saved from hishonor; let us in this solemn presence renew our pledges to aid and assist those whom they have left among us a sacred charge upon a nation's gratitude, the soldier's and sailor's widow and orphan.

It is the purpose of the Commander-in-Chief to inaugurate this observance with the hope that it will be kept up from year to year, while a survivor of the war remains to honor the memory of his departed comrades. He earnestly desires the public press to lend its friendly aid in bringing to the notice of comrades in all parts of the country in time for simultaneous compliance therewith.

Department commanders will use efforts to make this order effective.

By order of

JOHN A. LOGAN,

Commander-in-Chief

N.P. CHIPMAN,

Adjutant General

Official:

WM. T. COLLINS, A.A.G.

Sunday, May 29, 2005

Ebay Test Prep.....

And the American Board of Surgery doesn't take too kindly to it:Surgery board changing rules after doctor sells test answers

Used to be if you failed you could go and review your test with the correct answers. Seems as if this individual's entrepreneurial spirit took over:

There was no prohibition about discussing "scenarios" that are presented during oral exams when I took them. I used collections of scenarios that had been passed down from resident to resident in my program. They consisted of "Dr. X was in the first room and the first patient was a....." the scenario was discussed and the examinee gave their thoughts about how they thought they did. I used them, wrote about my experience, and included them for posterity.

So far, no subpoena for me.

H/T to Kevin |

And the American Board of Surgery doesn't take too kindly to it:Surgery board changing rules after doctor sells test answers

The American Board of Surgery has revised its testing policies after a doctor who failed a certification exam went back to review his test, wrote down the answers to dozens of questions and then put them up for sale on an Internet auction site.

The Philadelphia-based board, which has certified tens of thousands of surgeons nationwide, found out last summer that 86 questions used on its 290-question multiple-choice exam were listed on eBay. Questions used on the exam are rotated from a large pool each year.

Used to be if you failed you could go and review your test with the correct answers. Seems as if this individual's entrepreneurial spirit took over:

These are the actual certifying general surgery board questions with correct answers, guaranteed to improve your test score," the auctioneer wrote in August 2004. "A friend of mine failed this written exam, paid the $100 sitting fee and flew to Philadelphia to review his test. ... Why take the chance at failing, getting a year behind your peers...? Get an advantage now!"The exams all have "do not copy questions" written all over them.

Craig Edward Amshel, a rectal specialist out of St. Augustine, Fla., failed the 2002 exam. But, as was the practice at the time, he was later allowed to review his test, alone, at the board's offices in downtown Philadelphia for several hours.Amateur. Hadn't this guy heard of camera phones? Imagine what he could have done! Anyhow the Board slapped him down pretty hard:

"I was able to take notes very quickly and wrote down about 100 questions with the correct answer," Amshel wrote in an e-mail to a person posing, on the board's behalf, as someone preparing to take the 2004 exam. "Believe me, I was quite thrilled when I took the test last year as some questions were verbatim."

Amshel, who passed the 2003 test, has had his board certification revoked. Last fall, the board sued Amshel in federal court in Philadelphia, alleging copyright infringement and civil theft.

As part of a settlement last month, Amshel agreed to pay $36,000, the estimated cost of assembling teams of surgeons to go through the process of creating and testing new questions.

There was no prohibition about discussing "scenarios" that are presented during oral exams when I took them. I used collections of scenarios that had been passed down from resident to resident in my program. They consisted of "Dr. X was in the first room and the first patient was a....." the scenario was discussed and the examinee gave their thoughts about how they thought they did. I used them, wrote about my experience, and included them for posterity.

So far, no subpoena for me.

H/T to Kevin |

Thursday, May 26, 2005

Thursday, May 19, 2005

Tales From the Trauma Service XI ......

A husband and wife, t-boned on the wife's side of the vehicle. She complains of abdominal pain and is hypotensive. She does not respond to fluids or transfused blood. She has a minor pelvic fracture and some free fluid on FAST. Off to the OR...

About 2000cc of blood within the peritoneum. Spleen, large and small bowel, and stomach all OK. A small hematoma surrounding the pelvic fracture. The edge of the right lobe of the liver was pendulous. The dome of the liver was without injury. Inspection of the posterior segment demonstrates a large laceration extending into the porto-caval region.

This is when the wheels begin to come off.

At this time the patient develops EKG changes and bradycardia. I pack the injury off and occlude the aorta. After some CPR, defib, and drugs we regain a pulse and an adequate BP. Her PT was 20 when we hit the room and now her temp is 92 degrees. I repack the RUQ and close her with a VAC. She arrests again before we can get her to the ICU, but again drugs and CPR do the trick. Up to the unit where she codes again and despite 30 minutes of ACLS magic, she expires.

In the meantime, her husband is undergoing his evaluation. And the stab wound to the chest that came in before these two still needs a chest tube. The husband is hemodynamicaly stable and complains of right flank and back pain. The CT of the husband's abdomen:

Some duodenal thickening and periduodenal fluid (yellow).

Uh-oh, is that free air I see? (yellow again)

Another image, fluid at the blue line, air at the yellow.

The radiologist recommended that the study could be repeated in a few days. I don't thinks so. I repeat it a few hours later with oral contrast:

More fluid seen at the blue lines and contrast within the area that held free air earlier.

Air and contrast at the yellow area. SO a duodenal injury cannot be ruled out. Duodenal injuries are troublesome because they are difficult to diagnose, can be devastating if undiagnosed promptly, and it is an unforgiving organ to repair. The mortality and morbidity increase almost twofold if diagnosis is delayed over 24 hours. Surgical wisdom tells us that the reason God put the duodenum and pancreas posteriorly is that so surgeons wouldn't mess with it. So off I go on a journey through God's country.

Upon opening a fair amount of turbid fluid was seen. A right-sided medial visceral rotation was performed. The abdomen was explored and no other injury was found. The duodenum was Kocherized (rotated to the left) and what do I find?

Sorry it's blurry. Black line is the IVC, light blue lines are the duodenum, green line the posterior surface of the pancreas, and the dark blue line a duodenal diverticulum, which was the site of the rupture. Yahoo. Now what to do about repair? Fortunately the injury itself was able to be repaired primarily, but the trick is what to do to protect the repair long enough for it to heal. Obviously a closed-suction drain was placed. I opted for pyloric exclusion and gastrojejunostomy. The pylorus was sewn shut with a heavy PDS and a Billroth II-type gastrojejunostomy was performed. A feeding jejunostomy was also inserted. Here is a diagram:

The idea is that the pylorus will remain closed long enough for the repair to heal. This sort of operation takes time and in an unstable patient who is cold and coagulopathic time is a luxury you may not have. In that case damage control with repair and wide drainage is your primary move. He is doing fine so far.

A husband and wife, t-boned on the wife's side of the vehicle. She complains of abdominal pain and is hypotensive. She does not respond to fluids or transfused blood. She has a minor pelvic fracture and some free fluid on FAST. Off to the OR...

About 2000cc of blood within the peritoneum. Spleen, large and small bowel, and stomach all OK. A small hematoma surrounding the pelvic fracture. The edge of the right lobe of the liver was pendulous. The dome of the liver was without injury. Inspection of the posterior segment demonstrates a large laceration extending into the porto-caval region.

This is when the wheels begin to come off.

At this time the patient develops EKG changes and bradycardia. I pack the injury off and occlude the aorta. After some CPR, defib, and drugs we regain a pulse and an adequate BP. Her PT was 20 when we hit the room and now her temp is 92 degrees. I repack the RUQ and close her with a VAC. She arrests again before we can get her to the ICU, but again drugs and CPR do the trick. Up to the unit where she codes again and despite 30 minutes of ACLS magic, she expires.

In the meantime, her husband is undergoing his evaluation. And the stab wound to the chest that came in before these two still needs a chest tube. The husband is hemodynamicaly stable and complains of right flank and back pain. The CT of the husband's abdomen:

Some duodenal thickening and periduodenal fluid (yellow).

Uh-oh, is that free air I see? (yellow again)

Another image, fluid at the blue line, air at the yellow.

The radiologist recommended that the study could be repeated in a few days. I don't thinks so. I repeat it a few hours later with oral contrast:

More fluid seen at the blue lines and contrast within the area that held free air earlier.

Air and contrast at the yellow area. SO a duodenal injury cannot be ruled out. Duodenal injuries are troublesome because they are difficult to diagnose, can be devastating if undiagnosed promptly, and it is an unforgiving organ to repair. The mortality and morbidity increase almost twofold if diagnosis is delayed over 24 hours. Surgical wisdom tells us that the reason God put the duodenum and pancreas posteriorly is that so surgeons wouldn't mess with it. So off I go on a journey through God's country.

Upon opening a fair amount of turbid fluid was seen. A right-sided medial visceral rotation was performed. The abdomen was explored and no other injury was found. The duodenum was Kocherized (rotated to the left) and what do I find?

Sorry it's blurry. Black line is the IVC, light blue lines are the duodenum, green line the posterior surface of the pancreas, and the dark blue line a duodenal diverticulum, which was the site of the rupture. Yahoo. Now what to do about repair? Fortunately the injury itself was able to be repaired primarily, but the trick is what to do to protect the repair long enough for it to heal. Obviously a closed-suction drain was placed. I opted for pyloric exclusion and gastrojejunostomy. The pylorus was sewn shut with a heavy PDS and a Billroth II-type gastrojejunostomy was performed. A feeding jejunostomy was also inserted. Here is a diagram:

The idea is that the pylorus will remain closed long enough for the repair to heal. This sort of operation takes time and in an unstable patient who is cold and coagulopathic time is a luxury you may not have. In that case damage control with repair and wide drainage is your primary move. He is doing fine so far.

Labels: Tales from the Trauma Service

|Tuesday, May 17, 2005

Tuesday, May 10, 2005

Monday, May 09, 2005

Fifty Laboratories....

From The Wall Street Journal on Friday:Canada South: Will Vermont pass the most radical health-care "reform" in American history? Looks like Vermont is on the verge of having a single-payer health plan. A look at the history:

No indication if this would go before the voters in a referendum or not. The final paragraph:

From The Wall Street Journal on Friday:Canada South: Will Vermont pass the most radical health-care "reform" in American history? Looks like Vermont is on the verge of having a single-payer health plan. A look at the history:

In its early days in the Union--after 14 years as an independent republic--Vermont was a bastion of 18th-century radicalism dedicated to principles of "liberty and property." But shaped by the state's traditional town-meeting democracy, succeeding generations of Vermonters tempered this radical individualism. Until recently, however, Vermonters had steadfastly resisted big-government collectivism.But the Vermont house has approved a program which would:

This great leap forward into socialized medicine can be traced to the governorship of Madeleine M. Kunin (1985-90). She was committed to a Canada-style single-payer system. But her plan faded as revenues declined, and she ultimately settled for providing health services to needy children age 6 and under. But the single-payer concept would rise again.

In August 1991, when Gov. Kunin's Republican successor Richard Snelling died in office, part-time lieutenant governor and physician Howard Dean suddenly found himself Vermont's chief executive. Gov. Dean quickly distanced himself from the single-payer idea he had supported, favoring instead something called "regulated multipayer." Translation: Hillarycare.

Gov. Dean convinced the 1992 legislature to create a Health Care Authority to come up with two proposals: a single-payer plan and a regulated multipayer plan. But when it came time for a House vote in 1994, political support for a big-government solution had evaporated. Health care "reform" died ignominiously after a 7-0 vote in the Senate Finance Committee, and the Health Care Authority was abolished in 1996.

From 1995 until late 2004, health care "reform" in Vermont consisted of Gov. Dean's constant expansion of Medicaid to higher income workers, known as the Vermont Health Access Plan. Since the plan's costs rose much faster than the revenues assigned to pay for it, Gov. Dean financed the expansion by progressively underpaying doctors, dentists, hospitals and nursing homes. His successor, moderate Republican Jim Douglas, ruefully announced in his 2005 inaugural address that the state was headed for a $270 million Medicaid shortfall by 2007.

The proposed solution was universal coverage for "essential" services as defined by legislative committee. The state's 12 hospitals would be subjected to a binding "global budget." Doctors and other providers would be compensated on a "reasonable" and "sufficient" basis, in light of bureaucratically established "cost containment targets." Private health insurance for essential services would be abolished. The new system would be paid for by $2 billion in new payroll and income taxesSounds much like the proposal rejected in Oregon back in 2002.

No indication if this would go before the voters in a referendum or not. The final paragraph:

All of this would seem to be a tempest in a very small teapot, but for one thing: Over the past 30 years, Vermont, with a liberal majority, a hive of activist left-wing organizations, and a press corps largely hostile to anything smacking of conservatism, has become the nation's premier blue-state testing ground for virtually every imaginable liberal proposal. Putting single-payer health care in place in Vermont would be an enormous breakthrough for the left. This year its advocates are closer to victory than ever before. If they ultimately succeed, the reverberations will be felt from coast to coast.To which I say, go ahead, let them do it. It's easy for me to say it since I don't live in Vermont. The beauty of the federalist system is that the states can serve as trial group. Let Vermonters live a few years under a single-payer system. If it works, great. If it does literally turn Vermont into "Canada South" with waiting lists, rationing, and provider emigration then maybe the Kool-Aid won't taste so good. We're all for evidence-based medicine aren't we? |

The 80-hour Workweek and Operative Experience......

From the Journal of the American College of Surgeons:Impact of Work-Hour Restrictions on Residents’ Operative Volume on a Subspecialty Surgical Service

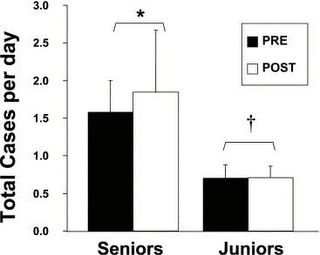

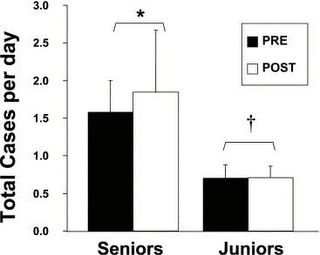

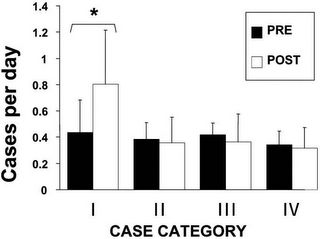

Data from the 2002 and 2003 academic years were compared. The senior residents were PGY 3&4 and the juniors were PGY 1&2. Procedures were broken down by class as well:

A slight but insignificant increase of senior level cases after the implementation of the rules. Now the operative experience, by class, of senior residents:

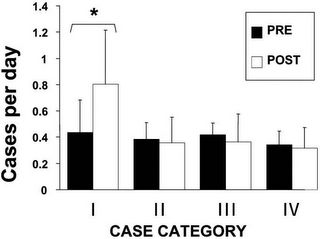

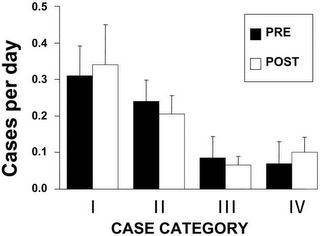

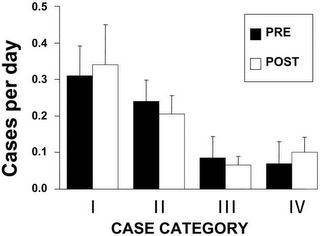

The vast majority of the increase comes from a large increase of the "minor cases". The p value for that increase was 0.03. Now for the junior residents:

Again some difference but nothing statistically signifigant. This program has done much to comply with the hour limits:

From the Journal of the American College of Surgeons:Impact of Work-Hour Restrictions on Residents’ Operative Volume on a Subspecialty Surgical Service

Background

Whether the 80 hours per week limit on surgical residents’ work hours has reduced the number or variety of cases performed by residents is unknown.

Study design

We quantified residents’ operative experience, by case category, on a pediatric surgical service. The number of senior and junior residents’ cases were compared between residents from the year before (n = 47) and after (n = 44) the 80-hour limit. Residents also completed a questionnaire about their operative and educational experience. As an additional dimension of the educational experience, resident participation in clinic was assessed. Student’s t-test was used.

Results

Total number of cases performed either by senior (before, 1.58 ± 0.42 versus after, 1.84 ± 0.82 cases/day) or junior (before, 0.70 ± 0.21 versus after, 0.71 ± 0.15) residents has not changed (p = NS). Senior residents’ vascular access and endoscopy rate increased; other categories remained stable. Residents’ perception of their experience was unchanged. But residents’ participation in outpatient clinic was significantly decreased (before, 66.0% ± 14.7% versus after, 17.0% ± 19.9% of clinics covered, p < 0.005).

Conclusions

The 80-hour limit has had minimal impact on residents’ operative experience, in case number and variety, and residents’ perceptions of their educational experience. Residents’ reduction in duty hours may have been achieved at the expense of outpatient clinic experiences.

Data from the 2002 and 2003 academic years were compared. The senior residents were PGY 3&4 and the juniors were PGY 1&2. Procedures were broken down by class as well:

Category I included all endoscopic procedures and vascular access procedures. Category II included simple, open surgical procedures. Major open procedures—both abdominal and thoracic—were placed into Category III. Category IV included all minimally invasive procedures.The residents filled out a questionnaire asking how certain aspects of the training program had changed due to the implementation of the 80 hour workweek. Items included educational quality of weekly conferences, quality of teaching received from surgical attendings, quality of teaching received from pediatric surgery fellows, amount of time available for reading, number of cases they had participated in, degree permitted to participate in cases, variety of cases exposed to during the month, rate the amount of independent decision making entrusted to them, degree to which residents had been involved in patient management, and overall, qualitative assessment of the educational value of rotation. No statistically significant difference was seen between the "pre-limit" and "post-limit" results. The differences were most apparent in the staffing of clinic and the case mix of the senior residents.

A slight but insignificant increase of senior level cases after the implementation of the rules. Now the operative experience, by class, of senior residents:

The vast majority of the increase comes from a large increase of the "minor cases". The p value for that increase was 0.03. Now for the junior residents:

Again some difference but nothing statistically signifigant. This program has done much to comply with the hour limits:

Before the ACGME mandate, residents in our program regularly worked well beyond 80 hours per week, a documented characteristic of many surgical residency programs. The dramatic changes necessitated by the 80-hour limit were unprecedented in our residency program. To comply with the requirements, after July 1, 2003, duty hours were closely monitored, and junior residents were required to leave the hospital at 10:00 am on the morning postcall. Even with this change, compliance with the 80-hour limit was not always achieved; and within a few months, the postcall residents had to be relieved of duty after 8:00 am. With this system, compliance with the 80-hour limit was achieved. We were surprised to find that the actual number of residents’ operative cases did not decrease. It may be that residents—to avoid a loss of operative experience—consciously made extra efforts to scrub into cases during their allotted time in the hospital, after the 80-hour limit took effect. Although Sawyer and colleagues have demonstrated that resident participation in surgery decreases with increasing frequency of call (every other night, versus every third or fourth night), frequency of call was unchanged in our study. Both before and after the 80-hour week, residents took call every third night.I wish I could take off at 8 AM on a post call day. The impact of case-mix and senior level resident participation can be significant as programs adapt:

Another point to be mentioned is that restructuring of the service took place in the last few months of the study, with removal of the senior from the service, leaving only junior residents under the supervision of the pediatric surgical fellows. This restructuring was a direct result of compliance with ACGME regulations. In the future, it is certainly conceivable that this type of restructuring of resident rotations may result in an overall decrease in number of cases performed by a senior-level resident on some subspecialty services. Data describing the operative experience of general surgery residents on surgical subspecialties such as pediatric surgery (for which the ACGME requires residents to log a specified number of cases) are very scarce.This is a phenomenon that is widespread. This study re-enforces the concept that upper level residents are more affected by hour limits that the junior ones:

We found that seniors performed significantly more vascular access and endoscopic cases after the 80-hour week was in effect. The explanation for this is not immediately apparent, but several previous studies have indicated that senior residents may be affected by work-hour limits more than juniors. In New York, 35% of residents reported that duties had been shifted from junior to senior residents to comply with work-hour limits. Our finding may represent this type of phenomenon, as cases in Category I are likely to be less highly sought after by upper-level residents than cases in the other categories. Our data suggest that a minor shifting of junior responsibilities to seniors may have occurred.So senior residents are performing cases usually reserved for the junior residents, because the junior residents all leave the hospital at 8 AM 1 out of every 3 days. So will the skills of these residents in two to three years be equal to the senior level residents that are rotating today? This would be a very interesting study to repeat in a few years. |

Saturday, May 07, 2005

Thursday, May 05, 2005

The Future of Surgery XI ........

Maria, of intueri, left a comment on this post concerning trauma surgery:

But less and less seem to want to eat the blood candy. In an address to the 2004 meeting of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma Dr. Steven Shackford, AAST president, gave a talk entitled:The Future of Trauma Surgery-A Perspective, published in the April edition on The Journal of Trauma. Dr. Shackford puts forth many of the challenges facing trauma and general surgery in the future:

The surgical generation gap:

Maria, of intueri, left a comment on this post concerning trauma surgery:

"Trauma surgery is one of the neatest fields in medicine. It's sickly fascinating."Or as Dr Yang in Gray's Anatomy puts it:""It's like candy! Only with blood, which is so much better!"

But less and less seem to want to eat the blood candy. In an address to the 2004 meeting of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma Dr. Steven Shackford, AAST president, gave a talk entitled:The Future of Trauma Surgery-A Perspective, published in the April edition on The Journal of Trauma. Dr. Shackford puts forth many of the challenges facing trauma and general surgery in the future:

The following observations made by Miller and Richardson regarding resident perceptions of trauma care have become icons with regard to perceptions about a career in trauma and critical care: (1) trauma care is increasingly non-operative, (2) trauma surgeons prepare patients for surgical procedures performed by other specialists, (3) trauma care has lower professional reimbursement than many other specialties, (4) trauma care increases the incidence of malpractice suits and increases the size of financial settlements of malpractice suits, and (5) trauma care increases the risk of AIDS and hepatitis C. In planning for the future, it is important to examine each of these perceptions to determine whether there are data to support them.In the study by Rogers cited above (abstract here) the billing of the radiologsts were higher than the trauma surgeons. As the authors themselves note:

Trauma care is increasingly non-operative. As Fakhry and colleagues pointed out in a survey of the membership of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma, the average resident experience per year on a trauma service is approximately 15 laparotomies, 6 diagnostic peritoneal lavages and 45 focused abdominal ultrasound exams. The operative experience of attending surgeons is also decreased. As pointed out by Wayne Meredith in his presentation to the Halstead Society, only 20% of trauma directors at Level I hospitals perform more than 100 trauma operations per year.

The perception that trauma surgeons prepare patients for operations by other surgical specialists has supporting data. Rogers and colleagues showed that there was a large disparity between work effort and financial reward among professionals. They demonstrated that trauma attendings provided about 70% of the work effort on trauma patients, but only billed about 25% of the professional fees. The majority of the fees were generated by the orthopedic surgeons and radiologists.

The perception that trauma care has lower professional reimbursement is difficult to validate. However, Esposito and colleagues in their study of trauma care in Washington State suggested that there be reasonable reimbursement for treating injured patients, but this depends on billing practices, documentation, and payer mix. Recent data suggests that any disparity in professional reimbursement between general surgeons and trauma surgeons is slight.

The data are sparse with regard to trauma care increasing the risk of malpractice suits with resulting increased financial settlement. However, in a Pennsylvania study cited by Esposito and coworkers comparing the malpractice claims of general surgeons to those of trauma surgeons, claims were more frequent against general surgeons than they were against trauma surgeons. When there was a finding for the plaintiff, trauma cases were settled for $25,000 less than general surgeons.

Finally, with respect to the perception that trauma increases the risk of AIDS and hepatitis, there are absolutely no supporting data.

This is especially striking considering the attending radiologists were not in-house at night, and many times read the films, which generated their professional charges, after the film had been read and acted on by the TS (trauma surgeon) the night before.

The surgical generation gap:

The perceptions of trainees are shaped not only by their professional experiences, but also by their culture. Most trauma care of today is provided by baby boomers and the trauma care of the future will be provided by Generation X, Generation Y and, the not-as-yet-born Generation Z. It is important in viewing the proposed changes in the specialty to examine the differences in the cultural background of the baby boomer and the cultural background of Generation X. For the most part, the parents of the baby boomers grew up during the depression. At that time, the most important aspect of one's life was having a job and holding on to that job. In effect, you were the job. Baby boomer physicians linked their altruism and their job and were zealously willing to make the necessary sacrifices, not only for their patients, but also for their job. This, you are the job mentality of the baby boomers created a rather narrow view of people who desired a more balanced lifestyle. As a result, baby boomers have been skeptical and critical about the commitment of Generation X to patient care.So what to do? Dr. Shackford takes the "emergency surgery" tack that is becoming increasingly popular:

Generation X, as compared with baby boomers, are individualists who are techno-competent and more flexible in their outlook. They desire immediate feedback, but do necessarily want definitive control. Most importantly, they desire balance in their life and define themselves by their personal life rather than by their job. Most Generation X students view surgery as a rigid, inflexible discipline with uncontrollable hours. Furthermore, Generation Xers desire personal time over financial reward when selecting a career. In fact, the amount of personal time is the major factor in career selection for Generation X of both genders. Generation X is not necessarily threatened by the hard work and the long hours, but they want defined time certain time off from their job for personal time. This desire has led to the selection of careers with a more controllable lifestyle.

I am of the opinion that all of these forces are creating another centripetal need to care for the whole patient that will be well received, not only by our patients, but also by payers, legislators, the American Board of Medical Specialties (as well as member boards in the surgical fields), and by the next generation of physicians. The centripetal need will necessitate the development of a specialty to care for the whole patient at all times. However, for this change to be embraced by all constituencies (patients, payers, policy makers, etc.) several key factors are essential. First, the change in our specialty should be motivated by altruism (as it was when the AAST was created). That is, this change is not about us but rather about our patients. Second, we must define our scope of practice and define a training paradigm that addresses this scope. The ad hoc committee has proposed a reasonable curricular program Third, the specialty must address the cultural issues and cultural desires of the next generation of surgeons. It may be that the acute care surgeon will be a surgical hospitalist who works 40 hours a week, divided into varying shifts (yes, shifts). Shift physicians of the future will no longer wear the scarlet letter of shift doctors that was once placed upon them by baby boomers. The dangers of shift medicine associated with the handing-off of patients are being reduced because we are developing systems, born by the resident 80-hour workweek that can capably address the problems with hand-offs. These problems are not entirely solved, but they soon will be. Having surgeons in-house 24-hours a day, capable of a wide variety of operations, will decrease length of stay, improve the efficiency of operating rooms, and decrease the cost of care. These changes have already been observed on the medical side of the house with the implementation of the hospitalist practice.31 Finally, the full development of the Acute Care Surgeon will only occur when there is complete collaboration by all of the professional societies that address the care of the injured and critically ill. That means that there must be collaboration among the AAST, the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma, the Western Trauma Association, the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma, the American Burn Association, and the Surgical Section of the Society of Critical Care Medicine. There is great power in such collaboration of professional organizations, as was demonstrated by the vascular surgeons. This power will provide at a seat at the table with regard to RVU assignment. It will allow the specialty to speak with one voice regarding legislative action that affects the care of critically ill and injured patients. With collaboration must come compromise with respect to curricular design, oversight of training programs, maintenance of certification, and turf issues.A tall order indeed. The emergence of a dedicated "emergency surgeon" may serve mainly to throw some, as we say down south, into the briar patch. In a paper, also in the April JOT:The Academic Trauma Center Is a Model for the Future Trauma and Acute Care Surgeon the group from Denver General describes their experience with such a system. The money quote:

A popular trend to increase the operative potential of the trauma service is to add nontrauma emergency surgery responsibilities. Although this appears to improve the trauma surgeon's operative experience and job satisfaction, reports thus far have focused on providing general surgery emergency services with limited coverage of vascular and thoracic nontrauma emergencies. Initial enthusiasm for this solution has the potential to be short lived because the majority of these surgical emergencies consist of draining soft tissue infections and excising necrotic gastrointestinal structures. Indeed, it can be argued that the trauma surgeon coverage of these surgical emergencies has a greater effect on the job satisfaction of the somnolent elective surgeon that is relieved of these responsibilitiesA panacea or long term cure? Unless some of the underlying issues are addressed, I fear the former.

Labels: Future of Surgery

|Tuesday, May 03, 2005

Is Evidence-Based Medicine Cruel????

From The New York Times, For a Hospital Stay, Only a Select Few Qualify:

Most of the problems the author has with the situation has to do with the inconvenience of it all:

So despite the evil, money-grubbing hospital treating this patient as an outpatient, she is doing just fine, without the complications she had before.

The real gem comes at the end:

The utilization of EBM will not only require a shift in the thought patterns of physicians, but in patients as well. Which will be harder to do? Stay tuned. |

From The New York Times, For a Hospital Stay, Only a Select Few Qualify:

The first time Mrs. Harris got a blood clot in her leg, back in 1998, she spent almost three weeks in the hospital. So when the other leg swelled up and began to throb last month, she came to the emergency room with a good-size suitcase, ready to stay.Is it because the outpatient treatment of DVT is advantageous? The author seems to imply that hospitals are "cruel":

As it happens, she never even got to unpack. She was riding back home in an ambulette barely 24 hours later with a sore leg, a bag of medicines to dissolve her new clot, and a vague sense of unease.

Hospitals in this country have become cruelly selective institutions of higher healing. Only the most qualified applicants are admitted (and then only a fraction of them get to unpack). The underlying financial principles are simple enough: most admissions generate a lump sum compensation. The simpler the illness, the smaller the sum. The longer the stay, the further it must stretch. The hospital thrums to a simple bottom line: get 'em in, get 'em out.The evolution of DVT therapy is examined:

Until a few years ago, a clot in the leg got you in and kept you there. In view of the worst possible outcome - that the clot would move to the lungs and cause respiratory collapse - observation and bed rest seemed essential. To dissolve the clot, one blood thinner had to be given by vein until a second oral one began to take effect, and levels of both needed frequent monitoring, lest spontaneous bleeding occur.Isn't this better? Most patients want to be at home and keeping them out of the hospital helps them avoid nosocomial infections. Early ambulation avoids deconditioning. The author seems to take issue with the economic aspects of EBM, that is how it is used to reduce the costs of treating an illness. This can be accomplished, as it has with thromboembolism therapy, by converting an illness previously handled on an inpatient basis to one handled as an outpatient. And cost is no small thing with DVT therapy as a Medline search of "outpatient dvt therapy" reveals many articles examining the cost benefits of outpatient therapy. There are some circumstances that may make Mrs. Harris a less than ideal candidate for outpatient therapy.

Then the technology changed. The intravenous medication was reformulated so that patients could inject it themselves, like insulin. The new drug did not need such careful monitoring. Studies showed that bouncing around at home with a clot in the leg was not particularly dangerous. Frequent blood tests were still necessary, but patients could get them as outpatients, and watch for bleeding themselves.

Unlike her disease, though, not too much about Mrs. Harris herself has changed since 1998. She still weighs close to 300 pounds, has a bad heart and stiff lungs, and lives a good hour from the hospital. She is still not very good at reading medication bottles or remembering drug doses.As the Retired Doc reminded us not all patients will fit nicely into the results of a randomized controlled trial. But none of the complaints offered up have much, if anything, to do with geography, obesity, or poor vision. The most concerning one, the GI bleed, is more often seen in treatment with unfractionated heparin (UH) than with the low-molecular weight version (LMWH). Often times LMWH is used in the inpatient setting because of improved safety and yes, less cost than intravenous UH, because of the decreased lab requirements.

She still cannot stand giving herself injections. She still hates having strangers (like visiting nurses) in her home. She is still the person who began to bleed from some unidentified site in her intestine while she was taking blood thinners the first time.

Most of the problems the author has with the situation has to do with the inconvenience of it all:

And so, it has been a hectic month for Mrs. Harris and her outpatient caretakers, of whom I am one, what with the missed injections, confused prescriptions, frantic phone calls, specially dispatched ambulettes and blood tests that are consistently off the mark. So far, she is doing fine despite it all. The rest of us are a little fatigued.(emphasis mine).

So despite the evil, money-grubbing hospital treating this patient as an outpatient, she is doing just fine, without the complications she had before.

The real gem comes at the end:

It is a cliché that once patients remove their street clothes and slip on hospital johnnies, they become invisible to medical staff, morphing from stockbroker, carpenter, musician into just one more generic body to process.Why? For what reason? To have her "outpatient caretakers" avoid a hectic month? Did this patient expect to go to the hospital for a vacation? EBM requires us to examine the patterns of our practice and ask ourselves why we do what we do. Can we do it better? Can we do it as well, or better at, perish the thought, a lower cost?

Exactly the same holds true, of course, when they slip on a disease. All their individuality tends to vanish behind its skimpy folds.

Would that someone had examined the lady with the blood clot in Room 9B24, discovered Mrs. Harris instead, overrode that inexorable get 'em in, get 'em out, and kept her right there.

The utilization of EBM will not only require a shift in the thought patterns of physicians, but in patients as well. Which will be harder to do? Stay tuned. |

Monday, May 02, 2005

At Least They Go to Class.....

Something I didn't do much of my first two years of medical school.

Grand Rounds XXXII hosted by Mudfud. |

Something I didn't do much of my first two years of medical school.

Grand Rounds XXXII hosted by Mudfud. |