Tuesday, November 30, 2004

From today's Wall Street Journal ($):In Malpractice Trials, Juries Rarely Have the Last Word

Earlier this year, a New York state jury awarded Elizabeth and John Reden $112 million in a medical-malpractice case filed on behalf of their brain-damaged daughter.On reason the do this is because the plaintiffs do not want a protracted appeal process that can delay payment, especially if the verdict exceeds the policy limits. Going after a physician's personal assets can be time consuming and expensive.

But the Redens didn't get $112 million. They got $6 million.

In the debate over medical-malpractice lawsuits, multimillion-dollar verdicts have become an important rallying cry for advocates of legislation to curtail jury awards. From emergency rooms to state houses to the White House, the advocates point to the heavy cost of large malpractice awards.

Behind the big dollar numbers, the reality is more complex. Many plaintiffs settle for less than a jury's verdict, to eliminate delays and the uncertainty of appeal. Sometimes, even before a jury rules, a plaintiff has signed an agreement that limits how much money actually changes hands.

The Redens, for example, hedged the outcome of their case through a common device known as a "high low" agreement. No matter what the jury ruled, the two sides agreed to settle for between $2 million and $6 million. Such agreements protect plaintiffs from a lengthy appeals process and typically set the top end of any potential award close to the limit on the physician's insurance policy.

So why do the big judgments matter if they are reduced? The high judgments themselves can "raise the bar" for settlements:

Proponents of tort reform acknowledge that verdicts for plaintiffs are often reduced to amounts that are kept confidential. But even if the headline-grabbing numbers are never paid out, proponents of limits say, big jury awards create benchmarks that raise the costs of future settlements.The reduction of an award can sometimes be dramatic:

"The verdict amount for a given case sets the bar for the value of that type of case during future settlement negotiations on similar cases," says Lawrence E. Smarr, president of the Physician Insurers Association of America, which represents physician-owned or operated companies that insure an estimated 60% of the nation's doctors.

But Neil Vidmar, a Duke University law professor, and colleagues of his there and elsewhere have come up with estimates based on studies in several states. After examining a pool of 105 malpractice verdicts from 1985 to 1997 in the New York City area, they found that 44% of jury awards were reduced after the verdict. The eventual payments to plaintiffs were, on average, 62% of the awards. Prof. Vidmar says this estimate is "very conservative" because the data he looked at covered only a short time after the verdict. Had the time been longer, he says, the study would have likely found that more of the awards had been reduced.

Prof. Vidmar also found that the larger the award, the steeper the discount. Large malpractice verdicts in New York were typically reduced to between 5% and 10% of the original verdict amount. One case with a total award of $90.3 million settled for $7 million. Another award, for $65.1 million, was reduced to $3.2 million.

My insurance carrier, MAG Mutual, prides itself on their aggressive defense of a suit, but sometimes pride goes before the fall:

Emboldened by this success, insurance companies are often willing to roll the dice with a jury. This happened two years ago during a trial in Lenoir County Superior Court, in eastern North Carolina. In that case, the family of John Waters, a 66-year-old retired manufacturing worker, sued Kinston surgeon Wayne T. Jarman and others. Dr. Jarman allegedly misdiagnosed Mr. Waters's ruptured appendix, then went on vacation without making arrangements to monitor the man's condition. Seven weeks later Mr. Waters died, and his family filed suit.Oops!. This may serve as ammunition for the foes of tort reform as they can point out that the massive awards that are raised like bloody shirts are reduced. My argument would be that any award that equals or exceeds coverage limits is massive enough. The crisis is not seen in the 2 percent of medical costs made up of malpractice awards, it is in the individual practicioner who can't afford their liability coverage. |

Dr. Jarman denied the allegations, and the Waters family offered to settle the case for as little as $250,000, says Bill Faison, the Waters' attorney. But Dr. Jarman's insurance carrier, Atlanta-based MAG Mutual Insurance Co., refused.

MAG is one of the largest physician-owned malpractice insurers in the Southeast, and a leading proponent of tort reform. One piece of legislation it successfully opposed earlier this year was the Georgia Sunshine in Litigation Act, which would have made it difficult for insurers like MAG and others to keep medical-malpractice settlements confidential.

MAG is also highly successful in the courtroom. Last year, says the company, it won 84% of its trials. In court filings, the company acknowledged that its highest offer to Mr. Faison on Dr. Jarman's behalf was $75,000.

Mr. Faison rejected that offer and the case went to trial. After three weeks of testimony and two hours of deliberation the jury awarded Mr. Waters's family $4.5 million. This was the largest medical-malpractice verdict involving a physician in North Carolina in 2002, according to North Carolina Lawyers Weekly, a legal publication based in Raleigh.

Monday, November 29, 2004

The New York Times today has a story on the decreasing popularity of vaginal birth after a Caesarean section (VBAC): Trying to Avoid 2nd Caesarean, Many Find Choice Isn't Theirs. Now procedurally this is really not my cup of tea but I find the definition of "choice" put forth in the article to be largely in the eye of the beholder.

VBAC was very much en vogue when I was a medical student and women were encouraged strongly to give labor a try. The risk of uterine ruptured was thought to be acceptable.The notice, posted in her obstetrician's office in Lancaster, Calif., came as a shock to Danell Freeman: the local hospital would no longer allow doctors to deliver babies vaginally for women who, like her, had previously had a Caesarean section. Unless she changed doctors and hospitals, Ms. Freeman would have to have another Caesarean - something she had hoped to avoid.

Ms. Freeman is 29, pregnant with her fifth child. The first three were born normally, the fourth by Caesarean. "I don't like the idea of being cut open again," she said.

Women around the country are finding that more and more hospitals that once allowed vaginal birth after Caesarean, or VBAC (commonly pronounced VEE-back), are now banning it and insisting on repeat Caesareans. About 300,000 women a year have repeat Caesareans. The rate of vaginal births in women who have had Caesareans has fallen by more than half, from 28.3 percent in 1996 to 10.6 percent in 2003

Obstetricians estimate that there is a 1 percent chance that the old Caesarean scar will cause the uterus to rupture during a subsequent labor, which can cause dangerous blood loss in the mother and brain damage or death in the baby. A decade ago, the risk of rupture was thought to be 0.5 percent or less. The percentage of babies injured after a rupture is not known but is thought to be lowBut not everyone is happy with the pendulum swinging the other way.

Many women are willing to take the risk, and the hospitals' stance has become a charged issue, part of a larger battle over who controls childbirth. Some women say their freedom of choice is being steamrolled by obstetricians who find Caesareans more lucrative and convenient than waiting out the normal course of labor. Doctors say their position is based on concern for patients' safety.Read carefully how "freedom of choice is being steamrolled". The story compares the apples of the "more lucrative and convenient" primary c-section to the oranges of the more safety oriented VBAC. Research has shown many variables contribute to the decision-making process of when to perform a c-section: "convenience" (how evil), labor expectations of the mother (and her mother), and recent experience of the OB/GYN (read:litigation).

Some doctors and hospitals freely acknowledge that fear of being sued has driven their decisions. Hospitals say they cannot comply with guidelines issued in 1999 by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, which call for a doctor to be available "immediately" throughout active labor during such a birth, to perform an emergency Caesarean if needed. Previous guidelines had called for them to be "readily" available.The change in the ACOG guidelines has proven to be unworkable in many situations:

Half the hospitals in New Hampshire and Vermont have stopped allowing women who have had Caesareans to try normal deliveries, according to Dr. Peter Cherouny, an associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Vermont. A telephone survey by an advocacy group, the International Cesarean Awareness Network, found 300 hospitals around the country that had quit offering the deliveries.

Dr. Charles Lockwood, chairman of the department of obstetrics, gynecology and reproductive sciences at Yale and an author of VBAC guidelines issued by the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology, said alarms began to sound in the late 1990's.

"What precipitated this were reports in the literature and reports that came to the college itself about women who had ruptured their uterus, particularly in rural settings, with no doctor and no anesthesiologist around," Dr. Lockwood said. "Babies died, and women lost the uterus in some cases."

That prompted the obstetrics college to change its formal recommendations for vaginal births after Caesareans in 1999, saying a doctor should be immediately available during labor to perform an emergency Caesarean.

"That had a chilling effect," Dr. Lockwood said, particularly on hospitals in rural areas that did not have anesthesiologists available around the clock, and on doctors in solo practices who could not stay with a patient throughout her labor......Dr. George F. Lee, a former obstetrician who is an administrator at California Pacific Medical Center and a spokesman for the American Hospital Association, said that while VBAC had proved safe in carefully controlled studies, the risks were higher in the real world of everyday medical practice.

"We went from seeing a ruptured uterus once every several years to seeing half a dozen a year at our medical center," Dr. Lee said.

So results that play out well in the academic setting don't have the same effect in the private practice world, surprise, surprise. The fear that some in the medical profession have is that women who insist on VBAC will make another choice:

Some doctors worry that banning the procedure may lead women who have had Caesareans to try giving birth at home or in birthing centers that are not equipped to perform an emergency Caesarean if it becomes necessary. Doctors also say some women, determined to avoid a repeat Caesarean, have endangered themselves and their babies by staying at home in labor - or even staying in the hospital parking lot - until the last minute.Aren't these choices made by the women? And now for the advocates view:

"The real issue going across American right now is, what do we do?" Dr. Flamm said. "Hundreds of thousands of women a year now are coming to hospitals with a previous Caesarean, some in communities where every hospital has shut down its VBAC program. That's the issue. Some will go to a lay midwife and have a VBAC in their bedroom. A good number will do fine, but some will have horrendous outcomes."

Some women see a Caesarean as having an operation instead of giving birth, and feel it means missing out on life's most joyful rite of passage.Ms. Stratton has made her choice, it seems. What these patients want, it seems to me, is to have their choice trump everyone else's. What is the goal here? I thought it was for the safe birth of a healthy baby with a healthy mom to take care of it. How this goal was achieved should be secondary.

"I'm an earthy person," said Barbara Stratton of Baltimore, who had her first baby by Caesarean in 1999. "This is a womanly thing to me. I wanted to birth my baby. You have that taken away if you're lying in a room full of strangers and they cut your baby out of your abdomen.

"For some of us who really care about birth, it can completely crush you."

Ms. Stratton said that she hoped to have another child, and that if she does, "I'm going to VBAC and I'm doing it at home."

I admit my bias since I am: #1 a man, and #2 both of my children were Caesarean births. Mrs. Parker attempted labor with our first child but there was "failure to progress" and a c-section was required. Mrs. Parker and I discussed VBAC and she and I fell into this category:

As for his own patients, Dr. Schipper said: "I can't think of any who had major issues. By and large, the feeling was, 'Great, I don't have to make a decision, go ahead and do the C-section, I was agonizing about it anyway and who am I as a lay person to go against what you think?' "

Why shouldn't the choice of the physician or hospital carry some weight? There is always a risk/benefit calculus with such things. The physicians have found that the risk of VBAC (uterine rupture and the complications thereof) outweigh the benefit (patient satisfaction with natural childbirth). The VBAC advocates believe the benefits of a trial of labor and the "birth experience" outweigh the risks of VBAC. So much so that some, like Ms. Stratton, are willing to undergo delivery out of the hospital. Yet the choice of the provider is given short shrift. Patients change physicians all the time, such as when they do not get the prescriptions they want, and no one raises a fuss. But when a non-emergent procedure is not offered, much hue and cry ensues.

Speaking from personal experience, the decision to restrict one's practice (which is what is happening here) is influenced by many factors. You cannot become tunnel-visioned and forget that there are other patients than the one in front of you. The OB/GYN is faced with denying VBAC to the few patients that want it, or agreeing with it and if something goes awry, facing the consequences. What if they can't get liability coverage and have to move? Who will take care of their patients? What if there are no other OB/GYN's in town? Is it worth it for the satisfaction of a minority given the access problems associated with OB/GYN? Tough choices, but ones that are treated poorly by some in the article.

What about high-minded ideals of "service to the community"? Unfortunately nowadays it is a question of survival for many physicians. |

Or, how I spent my Thanksgiving.

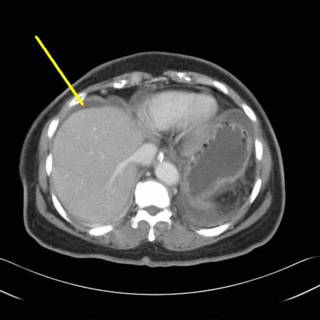

70-ish female with abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting. Prior history of hysterectomy and sigmoid colon resection. Medical co-morbidities of hypertension and diabetes. Exam on initial evaluation notable for mild tenderness without peritoneal signs. Hernias were felt and thought to be reducible. WBC of 8.3 without a shift. Initial plain films non too revealing:

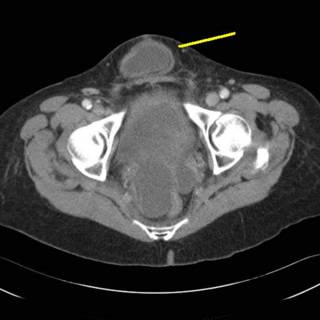

Clinically she kind of smoldered along for a day or so and we obtained a CT:

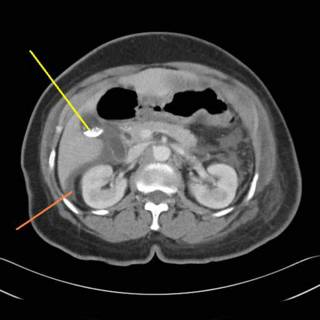

Some ascites, moving along:

More ascites and some gallstones:

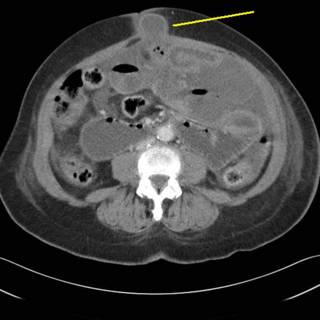

Ah-ha! Some bowel in the hernia defect:

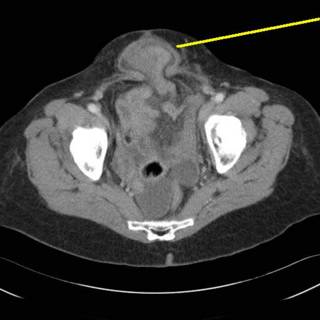

This is an additional defect lower in the pelvis.

This hernia appears to "lap over" the symphysis pubis. Given this CT scan, increasing WBC (up to 12.6) and worsening exam, it was decided to proceed to the OR.

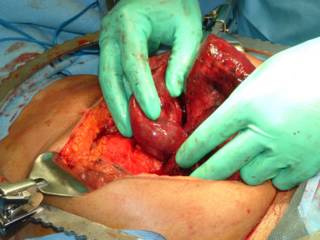

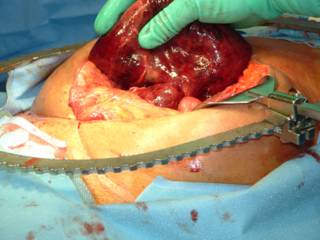

As usual, the following images may be offensive, proceed at your own risk:

]

]

]

]

]

]

]

]

]

]

]

]

]

]

You have been warned:

]

]

]

]

The bowel within the hernia defects was OK, this loop was separate from the defects.

There had developed an adhesive band between the colon and small bowel. The gangrenous loop had herniated through it. The segment was resected and an ansatamosis was formed. Exudative material was removed from the bowel and a cholecystectomy was performed.

She is slowly recovering |

Sunday, November 28, 2004

Dr. Code Blue puts forth another series of posts in his excellent "CSI Medblog" series in analyzing the death of Mary McClinton in a Seattle hospital. He provides a detailed list of questions (some provided by yours truly which have arisen from his examination of the facts in the media. As Moulder would say: the truth is out there.... |

Saturday, November 27, 2004

Georgia 19 Georgia Tech 13

Georgia 19 Georgia Tech 13

Nail-biter in Athens today. I have concerns for next year since David Shockley is due to be the starting quarterback next year. Wait and see I guess.

Now, which bowl game will it be?

These guys aren't too happy. |

From today's Atlanta Journal-Constitution : Georgia adds 4 to Congress' medicine chest

There's a doctor in the House. More than one, in fact, and two in the Senate.

With three physicians winning office in this year's congressional elections, including one from Georgia, there will be more doctors and dentists in Congress than at any time in the last four decades.

Georgia, with two physicians and two dentists among its 13 House members, now has more medical personnel serving on Capitol Hill than any other state.

Cobb County alone has two physician-lawmakers, both Republicans.

Rep. Phil Gingrey, a Marietta obstetrician, won a second term to represent the 11th District. Tom Price, a Roswell surgeon, was elected this month to represent the 4th District, which includes part of Cobb County as well as north Fulton and parts of Cherokee and DeKalb counties.

Georgia's dentists in Congress are Reps. John Linder of Gwinnett County and Charlie Norwood of Evans, an Augusta suburb. Both are Republicans.

Given the increased government involvement in health care issues, a trend seems to be growing:

The sudden bounty of doctors on Capitol Hill is no coincidence, according to candidates and political analysts. With the federal government increasingly involved in medical matters, from stem cell research to malpractice lawsuit reforms, physicians are finding new incentives to take a leading role in the political debate.Given the state of affairs today hopefully most of their efforts will be oriented towards tort reform. Physicians once upon a time were much more involved in politics on a national level:

"Physicians are becoming more politically astute. They have been woefully inadequate in that regard in the past," said Gingrey, who traveled the country campaigning for several medical colleagues running for office this year.

Two researchers from Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Chadd Kraus and Thomas Suarez, concluded in a new study that more doctors may be led to step into the political arena in the years ahead: "The current need for physician leadership in shaping health care is especially important."

The government's Medicare and Medicaid health care programs heavily influence doctor compensation.

Governmental oversight of the insurance industry and prescription-drug development also plays a significant role in health care options......

.....When the 109th Congress convenes in January, there will be at least 11 doctors and three dentists among the 535 lawmakers, the most since at least 1960. All but two of them are Republicans.

They include the Senate majority leader, Dr. Bill Frist of Tennessee.

Another doctor, Charles Boustany of Louisiana, is in a runoff for a House seat that will be decided Dec. 4 and could raise the total of doctors and dentists in Congress to 15.

Kraus and Suarez, in their study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association on Nov. 3, the day after the general election, said the recent increase in physician-lawmakers "may be indicative of a shift toward more direct influence of physicians in national politics."

Doctors accounted for 11 percent of the signers of the Declaration of Independence and 5 percent of the men who hammered out the U.S. Constitution, according to the researchers.Still not equal to the number of lawyers, however:

In the first 50 U.S. congresses, between 1789 and 1889, roughly 5 percent were doctors, the study found. That compares to 1 percent now.

Lawyers continue to dominate Capitol Hill much as they dominate state legislatures. About 235 of the 535 members of Congress have law degrees. Since 1960, nearly 45 percent of the people who served in Congress are lawyers.

"I do think there are a few too many lawyers," Gingrey said. "That really has hurt us on the tort reform issue."

Amen to that. |

Friday, November 26, 2004

Dispute over turkey blamed for stabbings

WORCESTER, Mass. - A man was charged with stabbing two relatives who allegedly criticized his table manners during Thanksgiving dinner.

Police said the fight broke out when Gonzalo Ocasio, Jr., 18, and his father, Gonzalo Ocasio, 49, reprimanded an uncle for picking at the turkey with his fingers, instead of slicing off pieces with a knife, the Worcester Telegram & Gazette reported Friday.

The uncle, Frank Palacious, 24, of Worcester, allegedly responded by stabbing them with a carving knife.

The father and son were being treated for stab wounds at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center.

A nursing supervisor said Friday she had no information on the younger Ocasio's condition. Police said he suffered stab wounds to the chest, back and right side. His father was treated for a stab wound in his arm.

Palacious is charged with two counts of domestic assault and battery with a dangerous weapon and assault with intent to murder, Detective Sgt. Thomas R. Radula said.

"You want me to use a knife?!? I'll show you how to use a knife!!!!"

Next on Jerry Springer.....

From the Boston Herald and Drudge

|

Thursday, November 25, 2004

I am thankful for: my family and friends, who have supported me throughout the years of education, training, long hours, and holidays away from home.

The men and women of the Armed Services who are stationed around the world to keep us safe.

The patients who make this more than a job sometimes.

The fact that I live in a country where a bitter, highly contested election can be resolved with, at worst, litigation and not the threat of a civil war.

The smiles and hugs of my children.

Georgia Bulldog football.

The internet and Blogspot which has allowed me to vent my spleen for almost a year and a half.

Online medical journals with free content (h/t Annals of Emergency Medicine)

The fact that Dunkin Donuts was open today so I could by doughnuts for my residents.

And finally, you the reader.

Have a safe and happy Thanksgiving!! |

Wednesday, November 24, 2004

One of the frequent theories of medical cost inflation that gets a great deal of play in the medical blogosphere is the insulation of consumers (patients) from the real cost of their care by insurance companies. Patients demand the newer, more expensive medication (Clarinex, Nexium) rather than the old reliables (Claritin, Prilosec) because they only pay the co-pay, and are spared the true cost. Well via The Commisar comes this commentary from Obsidian Wings and Marginal Revolution about how one medical procedure has actually fallen in cost. Mr. Tabarrok begins:

Everywhere we look it seems that health care is more expensive: prescription drug prices are increasing, costs to visit the doctor are up, the price of health insurance is rising. But look closer, even closer, closer still. Don't see it yet? Perhaps you should have your eyes corrected at a Lasik vision center.To which Mr. Holsclaw adds:

Laser eye surgery has the highest patient satisfaction ratings of any surgery, it has been performed more than 3 million times in the past decade, it is new, it is high-tech, it has gotten better over time and... laser eye surgery has fallen in price. In 1998 the average price of laser eye surgery was about $2200 per eye. Today the average price is $1350, that's a decline of 38 percent in nominal terms and slightly more than that after taking into account inflation.

Why the price decline in this market and not others? Could it have something to do with the fact that laser eye surgery is not covered by insurance, not covered by Medicaid or Medicare, and not heavily regulated? Laser eye surgery is one of the few health procedures sold in a free market with price advertising, competition and consumer driven purchases. I'm seeing things more clearly already

Of course he is a little carried away there. One reason prices are low is because laser eye surgery can be deferred, and you can shop around on the basis of quality and price. This isn't easily available to people having a heart attack, though it is available for long term or maintenance issues. It is worth noting that laser eye surgery has been steadily improving over the last few years. So as the price goes down and quality goes up, the overall value of the surgery becomes a better buy than even the declining price would show. His basic point remains--people are getting more for less in one of the few health care markets which is open to free competition. Maybe the post should entitled: "Good Point, to consider talking more about..."The commenters ask whether the costs of other pay-up-front procedures, such as breast augmentation, are falling in price. Not likely. LASIK has the advantage of being a highly automated, high volume, outpatient procedure done with minimal anesthesia. Few other procedures, covered or not, have those advantages. The new laparoscopic techniques that have come out for a wide variety of procedures; cholecystectomy, fundoplication, and colectomy, for example, have actually increased the cost of those procedures in the short run. This is primarily due to increased equipment costs, and sometimes (especially early in the learning curve) the operative time is increased. This is offset by the reduced length of stay and earlier return to activity compared to the more traditional open operations. With refinement of technique and reduced instrumentation cost, the overall cost of these could fall. But I'm sure reimbursement will be reduced before the true cost falls. |

From the Annals of Emergency Medicine via The New York Times:Trauma: For Medics, an Airway Quandary

Accident victims with brain injuries who were given breathing tubes by ambulance crews before they got to the hospital were four times as likely to die as a result of the accident as those given the tubes later, a new study finds. They were also more likely to suffer neurological problems.The wonderful folks at Annals graciously provide free access to the article Out-of-hospital endotracheal intubation and outcome after traumatic brain injury here:

The researchers, writing in this month's Annals of Emergency Medicine, based their findings on more than 4,000 patients who had been intubated in or out of the hospital.

While those who were given the tubes by ambulance crews appeared to have been more severely injured than those who were not - and as a result, more likely to die - the association between a higher mortality rate and out-of-hospital intubation remained even when this was factored out, the study said. Still, the researchers wrote, "We do not believe that the correct clinical interpretation is to defer out-of-hospital endotracheal intubation."

Instead, they said, future research should look at what may be going wrong when the practice is done in the field. One possible explanation is that paramedics are not allowed to administer the same drugs that doctors use when putting the tubes in.

The study also said that paramedics had less training with the tubes than doctors and that it was not uncommon for the tubes to be inserted wrong.

The study was led by Dr. Henry E. Wang and Dr. Donald M. Yealy of the University of Pittsburgh. The tubes are often given to people with brain injuries to keep their airways free and, the thinking goes, to reduce the risk of further brain injury caused by lack of oxygen.

Study objective: Previous studies disagree about the effect of out-of-hospital endotracheal intubation on traumatic brain injury. This study compares the effects of out-of-hospital endotracheal intubation versus emergency department (ED) endotracheal intubation on mortality and neurologic and functional outcome after severe traumatic brain injury.So the authors analyzed reports from the Pennsylvania trauma registry and found that patients that were intubated in the pre-hospital setting were four times as likely to die than patients with in-hospital intubation. While the out-of hospital intubated patients were sicker, the authors use some statistical modeling to correct for that. The authors studied patients with head and neckAbbreviated Injury Scale scores of three or greater. The study is provocative but does carry some limitations, some of which the authors acknowledge. The retrospective nature of the study being the largest one. Theories are put forth to explain the difference such as the limited experience of prehospital personnel in obtaining an airway, and the use of pharmaceutical adjuncts available in the hospital. No data was available to the registry about failed pre-hospital intubations attempts, which would obviously worsen outcomes.

Methods: From the 2000 to 2002 Pennsylvania Trauma Outcome Study (a registry of all patients treated at trauma centers in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania), adult patients with head/neck Abbreviated Injury Scale score of 3 or greater and undergoing out-of-hospital endotracheal intubation or ED endotracheal intubation were included. Transferred patients were excluded. The primary outcome was death (on hospital discharge). The secondary outcomes were neurologic (good versus poor, inferred from discharge to home versus long-term care facility) and functional outcome (determined from a Functional Impairment Score). The key exposure was endotracheal intubation (out-of-hospital endotracheal intubation versus ED endotracheal intubation). Using multivariate logistic regression, odds estimates for out-of-hospital endotracheal intubation were adjusted using age, sex, head/neck Abbreviated Injury Scale score, Injury Severity Score, mechanism of injury (penetrating versus blunt), admission systolic blood pressure, mode of transport (ground only versus helicopter or helicopter+ground), and the use of out-of-hospital neuromuscular blocking agents. A propensity score adjustment accounted for the potential effects of preexisting conditions, inhospital complications, and social factors (drug and alcohol use, race, and insurance coverage).

Results: There were 4,098 patients with head/neck Abbreviated Injury Scale score of 3 or greater who received either out-of-hospital endotracheal intubation (n=1,797, 43.9%) or ED endotracheal intubation (n=2,301, 56.1%). Adjusted odds of death were higher for out-of-hospital endotracheal intubation than ED endotracheal intubation (odds ratio [OR] 3.99; 95% confidence interval [CI] 3.21 to 4.93). Out-of-hospital endotracheal intubation was associated with an increased adjusted odds of poor neurologic outcome (OR 1.61; 95% CI 1.15 to 2.26), moderate or severe functional impairment (Functional Impairment Score 6 to 15; OR 1.92; 95% CI 1.40 to 2.64), and severe functional impairment (Functional Impairment Score 11 to 15; OR 1.80; 95% CI 1.29 to 2.52).

Conclusion: Out-of-hospital endotracheal intubation was associated with adverse outcomes after severe traumatic brain injury. The implications for current clinical care remain undefined

The paper and an accompanying editorial suggest:

The current findings, along with the results from other recent studies, should compel us to aggressively investigate out-of-hospital intubation for severe traumatic brain injury. Wang et all note that "... a logical-but risky and controversial-direction would be to conduct a controlled clinical trial randomizing patients with traumatic brain injury to either out-of-hospital endotracheal intubation or no out-of-hospital endotracheal intubation." We must ask, risk to whom? The mounting body of evidence suggests that out-of-hospital endotracheal intubation for patients with traumatic brain injury is not beneficial, and may be harmful. If our current out-of-hospital airway management protocols, or the training and supervision of our out-of-hospital providers results in worse outcomes for patients with traumatic brain injury, there is more "risk" with continuing business as usual than in performing definitive research in this area.Such a "risky and controversial" trial concerning resuscitation methods has been done before and the subject is still one of debate ten years later. I agree with the editorialist, if things are this bad now, what have we got to lose by putting on a trial? |

Surprising endorsement from the Guardian as one of the "Six of the best health and medicine blogs" along with Dr. Charles, Random acts of Reality, Derek Lowe, Doing Less Harm, and a link-lessGeena. Although to them I would be Mr. Parker. |

Tuesday, November 23, 2004

Grand Rounds IX hosted this week by Shrinkette.

Share with the group. |

This Washington Post article was reprinted in my local paper over the weekend:Dispelling Malpractice Myths:

Myth No. 1: The medical malpractice crisis is someone else's problem, not mine.Unfortunately the "limited extent allowed" is very limited indeed. A medical practice is one of the few businesses that cannot pass along its' increased costs to the consumer. Sometimes it takes drastic action such as what happened in West Virginia to bring this point home.

Premiums paid for malpractice insurance directly affect everyone's access to needed care and the cost of this care. Some excellent doctors are leaving practice in the face of unaffordable insurance premiums. Others are cutting back on the services they offer. To the limited extent allowed, doctors and hospitals pass increased malpractice insurance expenses on to patients and their health insurers.

If we don't fix the problems with the malpractice system, you may lose your doctor. You certainly will pay more for your care.

Myth No. 2: We need to preserve the current legal system to guarantee a fair hearing and provide compensation for patients harmed by the health care system.This is my biggest problem with the system, that a lay jury is asked to decide very complicated questions regarding medical liability and standards of care. They are asked to draw the line between negligence and an unexpected bad outcome. Very rarely does a "slam-dunk" case make it to a jury, those are most often settled out-of-court. The juries get the hard ones.

The medical justice system today is mostly random; it has become essentially a lottery. Hardly anyone seems to know this, although the facts are on the public record. A 1991 New England Journal of Medicine study found that nine out of 10 victims of disability-causing malpractice go uncompensated. That's right -- overwhelmingly, people harmed through medical mishaps are not compensated.

And a recent study by Harvard University researchers found that 80 percent of malpractice claims were filed against doctors who had made no error whatever. For instance, recent articles in scientific journals have documented that many, if not most, cases of birth-related cerebral palsy -- cases in which juries tend to be highly sympathetic to plaintiffs -- are not the result of malpractice by obstetricians. Juries often deliver sizable awards against providers who commit no errors for what are unfavorable, but random, outcomes of nature.

Myth No. 3: The malpractice system is necessary to punish and remove incompetent health care providers.The situation has gotten so bad that even medical staff officers are threatened with lawsuits for trying to separate the sheep from the goats. Outside review may be required but even that may not be the solution, since those organizations can be sued as well.

Unfortunately, the system that rarely provides just compensation for patients also perversely protects doctors who need to be removed from practice, by enabling them to sue other physicians who might step forward to question their competence. This undoubtedly has a chilling effect on whistle-blowing, and those who regulate doctors are often reluctant to suspend or revoke licenses without expert medical testimony.

Nor does the current liability system provide a way to make health care safer. Physicians, nurses and other professionals want to provide quality care, but they are human and make mistakes. What we need is a system that allows health care providers to work together to study errors and put practical improvements in place to prevent recurrences. The current system discourages doctors from talking about system failures for fear of being sued.

Myth No. 4: Malpractice costs are not a big deal -- they amount to less than 2 percent of total health care costs.The premium as percentage of income is the better measure here since the effect on the individual physician is what is driving the now and future access issues that are arising. I really don't' care about the percentage of total health costs the malpractice comprises. I care about how I'm going to pay my rent, staff, and salary after I write the check for my liability insurance, which has been called paying for the right to be sued.

The number sounds insignificant until you stop to consider that U.S. health care spending was a staggering $1.66 trillion in 2003 -- so we are talking of costs on the order of $16 billion to $32 billion.

In the case of Johns Hopkins Medicine, malpractice premiums as a percentage of physicians' total income have risen threefold over the past four years. In 2001 malpractice premiums were about 3 percent of total physician income at Johns Hopkins. They are nearly 10 percent today -- and growing.

The irrationality of our current medical justice system leads to the practice of "defensive medicine," in which doctors try to stave off lawsuits by ordering more tests than are medically necessary. Got a headache? You are as likely to get a CAT scan as a couple of aspirin. The added costs of defensive medicine are estimated at $50 billion to $100 billion per year.

Myth No. 5: The current malpractice insurance system is in crisis because insurance companies are trying to cover losses from unwise financial investments made during the dot-com boom.According to MAG Mutual's own figures the median awards are rising as well as the number of verdicts over $1 million.

Malpractice insurance rates are skyrocketing in large part because of the increasing size of malpractice awards. Nationally, median jury awards for medical malpractice doubled from 1995 to 2000, increasing from $500,000 to $1 million. Median out-of-court settlements also were up significantly during that time, rising 40 percent from $350,000 to $500,000.

Hospitals and doctors often settle cases out of court, even when they know they have done nothing wrong, because they fear putting their fate at the whim of unpredictable juries. Higher jury awards and settlements invariably mean higher malpractice insurance premiums and medical costs.

It was nice to see this issue get attention in the Post. Hopefully as state legislatures begin to meet in January some serious reform, moving beyond damage caps, will be passed. |

Friday, November 19, 2004

Hell of a week, starting off with a busy weekend on call (and a Georgia loss).

Getting a talk together that won't be given for a few months but the organizers wanted it this week.

I've had a flu-like illness for the past three days that has left me feeling like a warm pile of excrement.

We had some people from the state performing a redesignation visit which took up my whole day yesterday.

And, I was served with a lawsuit.

As Drudge would say, developing.....

|

Thursday, November 11, 2004

I've been posting mostly on social and other issues, while holding back on what people really visit this site for....posts with lots of cool pictures!

This was one of my partner's cases, but interesting. A teenaged girl, pregnant BTW, shot by a known assailant in the left temple. Entry just posterior to the left orbit. Here is a cut from the facial CT:

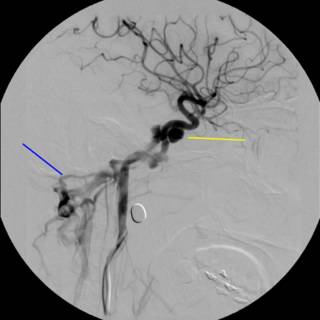

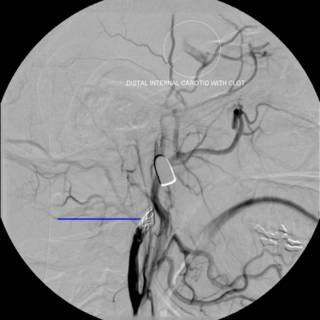

As you can see, the right wing of the sphenoid bone is fractured. Take a moment to contemplate what lives there. We sure did. Initial carotid angiogram:

The white line indicates the bullet. The yellow line indicates what was thought to indiate a traumatic aneurysm or dissection. We sent the image to academic neuroradiologists and they agreed with the diagnosis. The debate then became what to do with it. Given the location of the vessel, operative therapy was ruled out. We were able to take a gradual approach due to the fact that that patient remained asymptomatic. Anticoagulation was considered, to prevent any thrombus formation and propagation, but the patient had a small epidural hematoma. Repeat angiography....

Oooohh! Much bigger now, and for the parting gift...

What we have is a traumatic arterio-venous fistula. So our hand was kind of forced. The option of coil embolization was entertained at the beginning, but sort of a "hot potato" that no one wanted to touch. After we determined the patient had an intact circle of Willis, a balloon was inflated in the proximal internal carotid artery, and held in place for fifteen minutes. After a few rounds of "Mary had a Little Lamb" and squeezing a ball without difficulty, the problem was addressed:

As you can see from the last angio there was alreadt thrombus present. This case shows the advantage of youth and an intact circle of Willis. She was discharged and is doing well. |

Wednesday, November 10, 2004

Tennessee Governor Phil Bredesen, who promised during his campaign to fix TennCare, or end it, apparently chose the latter: Tenn. may dissolve state health care program:

Gov. Phil Bredesen announced Wednesday that the state plans to dissolve TennCare, cutting up to 430,000 people from the financially troubled supplemental Medicaid program barring a last-minute reprieve.There had been efforts to curb the generous benefits of TennCare, a program that was a blueprint for John Kerry's health care plan. These efforts were thwarted by lawsuits filed by "patient advocates":

The governor held out some hope for saving the program, announcing that he will try for seven more days to work out an agreement with legal advocates who have won several court decisions about the level of health care the state must provide to the 1.3 million TennCare enrollees.

Bredesen ran for governor two years ago with a promise to fix TennCare, whose $7.8 billion price tag was projected to mushroom in coming years, or to end it.

In the past, all TennCare participants had unlimited doctor visits and prescriptions. The stripped-down plan limited 270,000 of them to 12 doctor visits a year, 45 days in the hospital each year, eight outpatient hospital visits a year, 10 lab procedures or X-rays a year and six prescriptions a month.

Because of court challenges to the limited TennCare, Bredesen said, the only option would be to abandon it entirely unless the advocacy groups back off the challenges.

So, by fighting an effort to control costs and preserve the TennCare program, these lawsuits have served to eliminate the insurance coverage of 430,000 people. The floor-or-ceiling debate claims another casualty. |

I've been posting a great deal on the effect of residency program changes on the practice of surgery as a whole. One reason is that it is something that interests me. Another is the fact that there has been a great deal of primary material in the surgical literature. The Bulletin of the American College of Surgeons strikes again this month with How will limitations imposed on residents' work hours affect medicine?

The article begins with the well-known history of the Bell Commission and the implementation of the guidelines by the ACGME:

Over time, the ACGME hopes to gather information from the New York State experience to support the thesis that working excessively long hours negatively affects the cognitive performance and function of house staff officers. Since New York State restrictions were instituted in 1989, studies have shown that patient care has neither diminished nor improved. Gradually, through prospective and retrospective studies, training programs in New York are gaining insights into the changes in residents' attitudes about the residency program modifications.Two things: even with the recent studies in the New England Journal of Medicine the "evidence based" case for the workweek limits has yet to be made. Secondly, the studies from New York themselves seem to be a wash. Moving along:

Considerable debate among hospital administrators, medical directors, department chairs, and teaching program directors has arisen over the implementation of these requirements. Those individuals who concur with the new directives and regulations believe that house staff fatigue correlates directly with physician error, depression, anger, and lack of compassion for patients. These advocates for reform see benefits in adjusting oncall schedules, recruiting and educating physician extenders, and scheduling "night float" residents responsible for overseeing patient care on the evening and night shifts.Night float programs have been used in primary care residency programs for years, and many surgical programs are beginning to utilize them. The difficulty of a surgical night float is that while a medical admission (DKA, for example) that comes in at one o'clock in the morning is evaluated and treated pretty much the same way as one that comes in at one in the afternoon. Elective surgery is almost always a 7AM to 5PM schedule. The "night float" resident misses out. With the increasing non-operative management of trauma patients the night float experience consists of emergency surgery (appendectomies) and trauma resuscitation.

Other members of the community oppose the new regulations, arguing that more patient transfers between physician caregivers will lead to increased medical errors. The critics of these regulations emphasize that a key goal of house staff training is to engender a sense of accountability and responsibility. They also express concern over the loss of professionalism among resident physicians who regard themselves as "hourly workers." Will these restrictions inhibit or, even worse, sever the unique bond between patient and physician that has been the foundation of our profession and the public's perception of us?

The controversy over the "sign out" is not likely to abate soon. In the surgical patient not only is there a risk for information loss, but in patients that are being followed by serial physical exam, a subtle finding may be lost on a "new" examiner that the initial physician may have picked up on. The authors opine:

Is a "night float" system the answer? Studies have demonstrated that a "night float" system (in which designated residents cover night call for a specific time period) may be more detrimental to good patient care than the present system in which the same team provides continual care. This implies that a team of physicians, although fatigued, knows a patient and the nuances of his or her care and is, therefore, better suited to upholding continuity of care than a well-rested team that is unfamiliar with the patient. The residents who are part of the "night float" system are frequently pulled from their time on research electives, which is all about education unrelated to the issues of hospital coverage.The patients of today, and the care they require, are vastly different than those of the past:

The stress and intensity of caring for patients in teaching hospitals is far greater now than in the past, creating disturbing shifts in the attitudes of residents. House staff work-hour reforms reflect a response to changes in medical care in America, including decreased length of hospital stay, advancements in medical technology, and increased severity of illness.This is one thing that the "old fogeys" of surgery need to remember. In the old days patients would come in days before planned surgery for medical work-ups, colon preparation, ect. The length of stay for operations such as herniorraphies and appendectomies ranged from days to weeks. Since these patients nowadays do well as outpatients, most of that care was just to "feed and water" them. The acuity of hospital inpatients has risen expoentially over the past 10-15 years or so. So while the residents of yesteryear were on call every other night and in the hospital 150 hours a week, the "level of intensity" was lower.

So how are the residents taking this?

A survey of residents enrolled in general surgery programs throughout New York State confirmed that most respondents attempt to comply with Code 405 regulations. Although the majority of residents find that these regulations improve their quality of life by decreasing their stress level, a significant number are convinced that the rules negatively affect their surgical training and the quality, intensity, and continuity of patient care. A predicted reduction in educational operative opportunities was considered detrimental. Concern about the transition to a shift-worker mentality was a prevalent theme. Interestingly, negative perceptions of the impact of duty-hour restrictions are more prevalent among senior residents and residents at academic institutions than among junior residents at community hospitals. As reported from an inhouse survey at New York Presbyterian Hospital, residents and faculty believe schedule changes have a deleterious effect on patient care.The paper's abstract may be found here with my take on it here. Now these are mainly academic arguments, the real nugget of this article, and one that ties it to the article discussed last month:

Surgeons in private practice will face many practical concerns regarding the eventual effect of ACGME guidelines on the surgical workforce. The availability of surgeons to care for patients presenting to emergency departments or needing elective consultations is a significant issue in private practice. The majority of surgeons currently practicing in both academic and nonacademic practices are extremely concerned that the new guidelines may adversely affect the expectations that young surgeons have regarding call coverage and continuity of care. Surgeons in communities throughout America feel that they have a moral and ethical responsibility to care for urgent and emergent problems, and this concept has been a very significant component of surgeons' training. The disparity between the 80-hour workweek during residency and the expectation that hospital staff surgeons may be pressured to provide every third night on call once they enter into practice may produce some significant discontent in young surgeons entering the private workforce. These new ACGME guidelines may produce expectations of structured time off that are incompatible with the demands of private practice. Surgeons in private practice, while acknowledging the shortcomings of the traditional Halsted hierarchy training system, remain wary of the long-term effects of the ACGME guidelines.This has been my main objection to the workhour limits, the "artificial reality" that it imposes on trainees, that in all likelihood does not exist in the "real world".

Labels: Future of Surgery

|Tuesday, November 09, 2004

Sunday, November 07, 2004

The perfect holiday gift: UK Christmas Idea -- Plastic Surgery Gift Vouchers

If larger breasts, fuller lips and fewer wrinkles are on the Christmas wish list, cosmetic surgery gift vouchers could be the answer.Plastic surgery, the gift that keeps on giving! |

The number of Britons going under the knife for finer features has rocketed this year and some private clinics have started offering the vouchers to cope with demand.

"Husbands buy them for wives, or daughters for their mothers," said Rebecca Johnson, a spokeswoman for Transform, one of the UK's biggest commercial cosmetic surgery groups, which has sold hundreds of the vouchers this year.

They range from 50 to 1,000 pounds ($90-1,800) and are mostly used for non-surgical procedures such as botox and skin peels, she added.

Friday, November 05, 2004

The New York Times brings us : Defining a Doctor, With a Tear, a Shrug and a Schedule

I had two interns to supervise that month, and the minute they sat down for our first meeting, I sensed how the month would unfold.Medical training is at a crossroad, which way will it go?

The man's white coat was immaculate, its pockets empty save for a sleek Palm Pilot that contained his list of patients.

The woman used a large loose-leaf notebook instead, every dog-eared page full of lists of things to do and check, consultants to call, questions to ask. Her pockets were stuffed, and whenever she sat down, little handbooks of drug doses, wadded phone messages, pens, highlighters and tourniquets spilled onto the floor.

The man worked the hours legally mandated by the state, not a minute more, and sometimes considerably less. He was seldom in the hospital before 8 in the morning, and left by 5 unless he was on call. He ate a leisurely lunch every day and was never late for rounds.

The woman got to the hospital around dawn and was on the move for the rest of the day. Sometimes she went home when she was supposed to, but sometimes, if one of her patients was particularly sick, she would sign out to the covering intern and keep working, often talking to patients' relatives long into the night.

"I am now breaking the law," she would announce cheerfully to no one in particular, then trot off to do just a few final chores.

The man had a strict definition of what it meant to be a doctor. He did not, for instance, "do nurses' work" (his phrase). When one of his patients needed a specimen sent to the lab and the nurse didn't get around to it, neither did he. No matter how important the job was, no matter how hard I pressed him, he never gave in. If I spoke sternly to him, he would turn around and speak just as sternly to the nurse.

The woman did everyone's work. She would weigh her patients if necessary (nurses' work), feed them (aides' work), find salt-free pickles for them (dietitians' work) and wheel them to X-ray (transporters' work).

The man was cheerful, serene and well rested. The woman was overtired, hyperemotional and constantly late. The man was interested in his patients, but they never kept him up at night. The woman occasionally called the hospital from home to check on hers. The man played tennis on his days off. The woman read medical articles. At least, she read the beginnings; she tended to fall asleep halfway through.

I felt as if I was in a medieval morality play that month, living with two costumed symbols of opposing philosophies in medical education. The woman was working the way interns used to: total immersion seasoned with exhaustion and adrenaline. As far as she was concerned, her patients were her exclusive responsibility. The man was an intern of the new millennium. His hours and duties were delimited; he saw himself as part of a health care team, and his patients' welfare as a shared responsibility.Who would you want as your physician? |

This new model of medical internship got some important validation in The New England Journal of Medicine last week, when Harvard researchers reported the effects of reducing interns' work hours to 60 per week from 80 (now the mandated national maximum). The shorter workweek required a larger staff of interns to spell one another at more frequent intervals. With shorter hours, the interns got more sleep at home, dozed off less at work and made considerably fewer bad mistakes in patient care.

Why should such an obvious finding need an elaborate controlled study to establish? Why should it generate not only two long articles in the world's most prestigious medical journal, but also three long, passionate editorials? Because the issue here is bigger than just scheduling and manpower.

The progressive shortening of residents' work hours spells nothing less than a change in the ethos of medicine itself. It means the end of Dr. Kildare, Superstar - that lone, heroic healer, omniscient, omnipotent and ever-present. It means a revolution in the complex medical hierarchy that sustained him. Willy-nilly, medicine is becoming democratized, a team sport.

We can only hope the revolution will be bloodless. Everything will have to change. Doctors will have to learn to work well with others. They will have to learn to write and speak with enough clarity and precision so that the patient's story remains accurate as care passes from hand to hand. They will have to stop saying "my patient" and begin to say "our patient" instead.

It may be, when the dust settles, that the system will be more functional, less error-prone. It may be that we will simply have substituted one set of problems for another.

We may even find that nothing much has changed. Even in the Harvard data, there was an impressive range in the hours that the interns under study worked. Some logged in over 90 hours in their 80-hour workweek. Some put in 75 instead.

Medicine has always attracted a wide spectrum of individuals, from the lazy and disaffected to the deeply committed. Even draconian scheduling policies may not change basic personality traits, or the kind of doctors that interns grow up to be.

My month with the intern of the past and the intern of the future certainly argues for the power of the individual work ethic. Try as I might, it was not within my power to modify the way either of them functioned. The woman cared too much. The man cared too little. She worked too hard, and he could not be prodded into working hard enough. They both made careless mistakes. When patients died, the man shrugged and the woman cried. If for no other reason than that one, let us hope that the medicine of the future still has room for people like her.

Thursday, November 04, 2004

Elizabeth Edwards Has Breast Cancer

- Elizabeth Edwards, wife of former Democratic vice presidential candidate John Edwards, was diagnosed with breast cancer the day her husband and Sen. John Kerry conceded the presidential race.

Spokesman David Ginsberg said Mrs. Edwards, 55, discovered a lump in her right breast while on a campaign trip last week. Her family doctor told her Friday that it appeared to be cancerous and advised her to see a specialist when she could.

She put off the appointment until Wednesday so as to not miss campaign time. Mrs. Edwards had a needle biopsy performed at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, where Dr. Barbara Smith confirmed the cancer, Ginsberg said.

He said the cancer was diagnosed as invasive ductal cancer. That is the most common type of breast cancer, and can spread from the milk ducts to other parts of the breast or beyond.

More tests were being done to determine how far the cancer has advanced and how to treat it, he said.

Ginsberg said spirits are high at the Edwards household. "Everybody feels good about it, that this is beatable," he said.

Edwards, who leaves his North Carolina Senate seat in January, said in a statement, "Elizabeth is as strong a person as I've ever known. Together, our family will".

My prayers are with Senator and Mrs. Edwards and I wish them well. |

I try not to do a great amount of political commentary here because there are those that do it far better than I. The lists of winners (President Bush, Republicans) and losers (Senator Kerry, Terry McAuliffe, mainstream media) are everywhere. Here are my two cents:

When Senator Zell Miller came out with his book, A National Party No More: The Conscience of a Conservative Democrat he wrote:

Once upon a time, the most successful Democratic leader of them all, FDR, looked south and said, "I see one third of a nation ill-housed, ill-clad, ill-nourished." Today our national Democratic leaders look south and say, "I see one third of a nation and it can go to hell."He was described as a traitor to his party. He was lambasted as "evil" for his speech at the Republican National Convention. Now, after the election, pundits are debating the steps the Democratic Party needs to take to expand their appeal. In an article today in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution Senator Miller takes a victory lap with I tried to tell you . . .

When will national Democrats sober up and admit that that dog won't hunt? Secular socialism, heavy taxes, big spending, weak defense, limitless lawsuits and heavy regulation — that pack of beagles hasn't caught a rabbit in the South or Midwest in years.

The most recent failed nominee for president stands as proof that the national Democratic Party will continue to dwindle. The South has gone from just one-fourth of the Electoral College in 1960 to almost a third today.

To put this in perspective, that gain is equal to all the electoral votes in Ohio. Yet there was not a single Southern state where John Kerry had any real chance. Would anyone like to place bets on the electoral strength of the South by 2012? Maybe they should tax stupidity.

When you write off centrist and conservative policies that reflect the will of people in the South and Midwest, you write off the South and Midwest. Democrats have never learned from the second or third or fifth kick of a mule. They continue to change only the makeup on, rather than makeup of, the Democrat Party.

Could have things been different? Look at this July 2003 post about the moderate Democratic governor who appointed Zell Miller to the Senate, Roy Barnes:

WILL THIS BE WHAT HELPS THE REPUBLICANS WIN THE WHITE HOUSE IN 2004?

Silly question? Well what got me started was the continued growing buzz over Howard Dean and his campaign's fund raising prowess over the internet. The sum of money raised means that Dean cannot be ignored, poor Sunday morning performance notwithstanding. Dean has really mobilized the democratic faithful, which makes him the opponent that the Republicans hope secures the nomination. But what does the Georgia flag have to do with it? Well the flag above lies over the political body of someone who could have been a serious contender for the nomination, a centrist southern democratic governor that doesn't have the baggage of another centrist southern democratic governor. The political career that the flag killed was that of former Georgia Governor Roy Barnes.....

The political columnist Bill Shipp wrote about Governor Barnes' rising star as a Democratic nominee in March 2001. However things fell apart and Mr. Barnes was defeated in November 2002. While some other factors contributed as well (displeasure with education reform and the "Northern Arc") the flag issue mobilized a lot of emotion in rural areas of Georgia and a tremendous amount of those voters expressed their displeasure by electing Georgia's first Republican governor since reconstruction. For his efforts Governor Barnes won a Profiles in Courage award from the Kennedy library. Mr. Shipp provides an excellent analysis of his remarks here.

I think that Governor Barnes did the right thing in changing the flag. It was a divisive symbol and not representative of a state who's capital is the "City too Busy to Hate". I think the Kennedy library rightly rewarded him. But the unintended consequences are present today....

More locally, the Republicans have taken control of the Georgia General Assembly for the first time since reconstruction. The crew at the Medical Association of Georgia are counting coup today:

The members of the Medical Association of Georgia are to be congratulated on the incredible victories across the state for medicine friendly candidates.There are high hopes for meaningful tort reform next year.

Of the candidates endorsed on MAG's General Election Ballot, 86.2% were successful in the Georgia Senate and over 95% were triumphant in the Georgia House. These outstanding results could not have been achieved without the grassroots involvement of physicians and generous contributions to MAG's Tort Reform Fund and GAMPAC. Physician contributions to GAMPAC allowed the organization to make over $250,000 in hard dollar contributions to pro-medicine candidates over the course of the 2004 election cycle.

Using money collected for the Tort Reform Fund, MAG was able to protect incumbents and help elect candidates that are champions of medicine using polling and direct mail. Many of these candidates were directly targeted by the Georgia Trial Lawyers Association and faced stiff opposition by trail lawyer candidates or their surrogates.

Senator Kerry is to be commended for his concession. I have no doubt that there were members of his inner circle that were pressing him to contest the results, but he wisely took the high road and bowed out with class. |

Tuesday, November 02, 2004

Last Thursday and Friday I engaged in my semi-annual self-flagellation as course director for the Advanced Trauma Life Support provider class. The class was made up of some local physicians seeking CME, some physicians that work in small community ED's that are in Big Hospital's referral area, and many of the residents in the family practice program in town.

The residents really irked me. I had discussed at length with their chief residents that the residents needed to be released from all clinical duties during the class. I still had residents showing up late and coming and going during the course to do god only knows what.

It got off to an inauspicious start with the course co-ordinator and I not connecting about who was available to teach until last Monday. I then had to go hat in hand to my partners (who had already scheduled elective cases) to get them to teach.

The ATLS course has a "surgical skills practicum" where the student performs certain procedures discussed in the course. These include chest tubes, pericardiocentesis, crichothyroidotomy, and diagnostic peritoneal lavage. In the past we have used goats for the surgical lab, but our goat supplier went out of business. We were able to quickly obtain the Trauma Man. IMHO it is an excellent device and much simpler and cleaner than the goats.

And to put the icing on the cake, one of the instructors that was going to lecture and test during Friday's session no-showed. This left me to give his lectures and to initially test with only three instructors. Another one had to leave at 5:30. So me and another instructor tested until 8:00.

Every once and awhile I will get an itch to put on another course but days like that quickly dissuade me.

|